Visits to the writing center and office hours provide students structured reflection and low-stakes feedback on scientific writing in an Introductory Biology course

Published online:

Abstract

Effective written communication of scientific concepts is a critical, but difficult skill for undergraduate STEM majors to acquire. Oftentimes, the grades of lab reports are negatively impacted by sentence structure and the failure to adhere to the traditional conventions of scientific writing. The goal of this learning strategy was to use student-centered, out of class assignments to allow students to reflect on their scientific writing and receive feedback on their traditional lab report from two campus resources. After a lecture describing the format of a lab report and how to utilize a rubric to write a lab report, students wrote a rough draft of their lab report using a substantive rubric to guide the content. In a structured visit with a peer writing tutor, students received feedback on sentence structure; and the inclusion of traditional conventions of a lab report such as a testable hypothesis, explanation of the results in relation to the hypothesis, and a description of the results and their variation in testable groups. After submitting and receiving a grade on their rough draft, the students reflected on the strengths and areas for improvement of their rough drafts followed by a discussion of questions that they had regarding the drafts with their instructor during office hours. This strategy guided the scientific writing process and encouraged students to reflect on the strengths of their writing and receive low-stakes feedback from different campus resources prior to the submission of a writing assignment.

Citation

Brooks YM. 2019. Visits to the writing center and office hours provide students structured reflection and low-stakes feedback on scientific writing in an Introductory Biology course. CourseSource. https://doi.org/10.24918/cs.2019.36Lesson Learning Goals

Adapted from the Visions and Changes Core Competencies (1) "Students will improve communication with others through scientific writing" through the guided formation of a traditional lab report within four areas:- sentence structure

- adherence to the conventions of a traditional structure of a lab report with special attention to: the inclusion of a testable hypothesis; summary and comparison of testable variable groups on the results section; and a biological explanation of the results that answer the testable hypothesis

Lesson Learning Objectives

- Students will be able to write a lab report that contains a descriptive title, complete and concise abstract, substantive and relevant introduction that includes a testable hypothesis, descriptive methods, description and comparison of results of various testable groups, biological explanation of the results that reflect the testable hypothesis, a conclusion that contains societal implications or scientific impact, and references cited in the document.

- Students will be able to self-identify weaknesses and strengths of their writing.

- Students will understand how to utilize office hours and the writing center to receive feedback on their lab reports.

Article Context

Course

Article Type

Course Level

Bloom's Cognitive Level

Vision and Change Core Competencies

Vision and Change Core Concepts

Class Type

Class Size

Audience

Lesson Length

Pedagogical Approaches

Principles of How People Learn

Assessment Type

INTRODUCTION

Effective written communication of scientific findings and comprehension of scientific literature are two main components of scientific literacy that should be represented in a bachelor's degree in a STEM field. However, this is a difficult feat to accomplish because students begin higher education with varying levels of scientific comprehension and writing skills (2). It has been argued that a freshman composition class does not prepare students for technical writing (3) in STEM fields. Instructors in many writing intensive STEM courses are unable to take time away from course content to teach scientific writing skills (4). Therefore, there is a need to incentivize of the utilization of campus resources to receive feedback prior to the submission of a scientific writing assignment.

Many colleges and universities have writing centers where students of any major can meet one-on-one with a peer tutor to discuss various aspects of the writing process. Such visits can provide students with low-stakes feedback to drafts of scientific writing assignments. However, voluntary visits to the writing center are not uniform across all student populations (5). To combat this, instructors have implemented mandatory visits to the writing center with much success. A previous study demonstrated that required visits to the writing center in a freshman writing course were positively correlated with students passing the writing course and increased the likelihood of visiting the writing center in subsequent semesters (6). Furthermore, 70% of students that were enrolled in a developmental writing course that included required visits to the writing center recommended that mandatory visits to the writing center should be incorporated into all developmental writing courses (7). These studies suggest that mandatory visits to the writing center are an evidence-based strategy that improves educational outcomes of early college students.

Besides the utility of the writing center, student-faculty interaction is paramount to high-impact educational practices (8). Attending office hours is a useful tool that can improve student learning. However, student participation in office hours is often underutilized due to the students' busy schedules, feeling intimidated by their professor, or lack of confidence (9). A previous study demonstrated that students who were encouraged to interact with their instructors in their first semester of college were less likely to withdraw from the institution (10). Also, students in lower and upper level political science courses who visited office hours were more likely to have higher grades (11). Therefore, these studies help support the suggestion by college-level instructors that visits during office hours should be required (12) so that students can build interpersonal skills with their instructors (13) while receiving low-stakes feedback on their coursework.

In this article, I describe a student-centered learning strategy to guide first year Biology majors in an Introductory Biology course in the writing of a traditional lab report. This multi-week strategy consisted mostly of out-of-class assignments such as a writing a lab report with guidance from a substantive rubric, self-reflections of the strengths and weaknesses of their report, and structured visits to the campus writing center and office hours to receive low-stakes feedback. The purpose of the substantive rubric was to ensure that the following conventions of a traditional lab report were included in the students' reports: a descriptive title, complete and concise abstract, substantive and relevant introduction, a testable hypothesis, descriptive methods, results that summarize and compare the test variable across treatment groups, a discussion that provides a biological explanation of the results and reflect the hypothesis, a conclusion that contain societal implications or scientific impact, and references cited in the document listed in a bibliography. The structured visit to the writing center allowed students to receive feedback on their adherence to the traditional aspects of a laboratory report with special attention to the inclusion of a testable hypothesis, summary and comparison of results from the different treatment groups, and biological explanation of the results that reflect the testable hypothesis. I focused on the above areas because these were areas of weaknesses that I routinely noticed in the scientific writing of Biology majors. The office hours visit was designed as a reflection to help students understand the strengths and areas of improvements of their rough draft and discuss what changes they will make to the document prior to the submission of the final draft.

INTENDED AUDIENCE

This strategy was designed for students in their first or second year at a comprehensive institution. I used this learning strategy for one section of a writing intensive introductory Biology laboratory course for Biology, Biochemistry, and Chemistry majors. There were 20 students in the laboratory section.

REQUIRED LEARNING TIME

This learning strategy spanned three days of in-class instruction, and four out-of-class assignments.

PREREQUISITE STUDENT KNOWLEDGE

Students should have knowledge of the scientific method.

PREREQUISITE TEACHER KNOWLEDGE

I coordinated this learning strategy with the director of the writing center. The director and I met with peer writing tutors to discuss their concerns and strategies to ensure successful interactions with the students. I reviewed the conventions of a traditional lab report with the tutors because not all tutors were STEM majors. I also made a list of common mistakes that the tutors and I have routinely observed in student writing. I included the list in a handout to help guide interactions between the tutors and the students.

SCIENTIFIC TEACHING THEMES

ACTIVE LEARNING

There were three learning methodologies that students used while completing the learning objectives. The first methodology was a creation of rough and final lab report based on an in-class experiment. The lab report included a descriptive title, complete and concise abstract, substantive and relevant introduction that included a testable hypothesis, descriptive methods, description and comparison of testable groups in the results, biological explanation of the results that reflected the testable hypothesis in the discussion, a conclusion that contained societal implications or scientific impact, and a bibliography that included only references cited in the document. The substantive rubric also provided guidance on what information to include in the lab report.

The second methodology was self-reflection. In preparation for the visit to the writing center, students wrote a reflection self-identifying concerns in their writing. Upon receiving a grade for the rough drafts of their lab reports and before the visit to office hours, students also completed another written reflection of the areas of improvements and strengths of the report as well as outlined questions regarding the assessment of their lab reports.

The third methodology was structured one-on-one interactions with a peer writing tutor and myself to provide students low-stakes feedback regarding the sentence structure and inclusion of the basic tenants of a well written laboratory report with special attention to a testable hypothesis, summary and comparison of testable groups in the results, and biological explanation of the results in the discussion that match the testable hypothesis.

ASSESSMENT

I assessed learning via multiple assignments including written reflections, one-on-one interactions with a writing tutor and myself, and the rough and final drafts of a lab report. I used a substantive rubric (Supporting File S1: Example grading rubric for the rough and final drafts of the lab report) to assess the rough draft and final drafts of the lab report. The rough and final drafts were 5 and 10% of the course grade, respectively. The final two assessments described below were assessed based on the completion of the tasks listed in the document and were worth a total of 3.6% of the course grade. For the second assignment, students self-evaluated three areas of concern in their lab reports that they would like to discuss with a writing tutor or with myself during office hours (Supporting File S3: Writing Center handout- guidance for visit to the writing center and Supporting File S4: Office Hours handout- guidance for office hours visit, respectively). Finally, students participated in one-on-one discussions first with a writing tutor and then with the instructor to receive feedback on their scientific writing and discuss any concerns regarding the lab report. During the writing center visit, students also had an opportunity to discuss if the lab reports contained a testable hypothesis, summary and comparison of testable groups in the results, biological explanation of the results in the discussion that match the testable hypothesis. They were also able to discuss any other component of the lab report. During the office hours visit, students could discuss the strengths and areas of improvements of their document and how they will edit it in preparation for submission of the final draft.

INCLUSIVE TEACHING

This assignment encouraged inclusive teaching by designing a student-centered learning strategy that catered to the writing skills of each student in an Introductory Biology course. The visit to the writing center (and the office hours visit, within reason) worked around the students' schedules. Additionally, the students were able to select a tutor that best complemented their learning style and personality.

LESSON PLAN

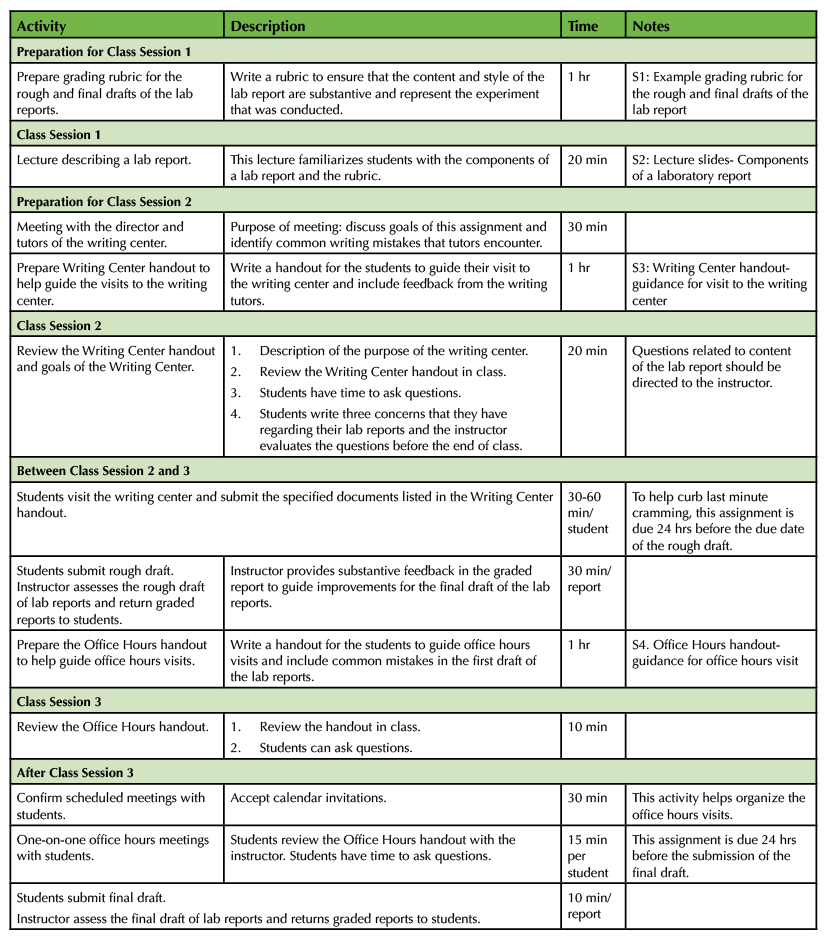

I utilized this learning strategy in an Introductory Biology lab course over three weeks (Table 1). The rubric that I used was expansive and contained specific topics of the introduction that this lab report should contain. Therefore, the grading rubric should be changed for another course.

Table 1. Scientific Writing - Teaching Timeline

PRE-CLASS PREPARATION

COORDINATION WITH THE WRITING CENTER

Coordination with the director and tutors of the writing center was necessary for the success of this learning strategy. The director and I met with the writing center tutors before the students' visit to discuss the goals of the assignment. This meeting included the following: an explanation of the overall structure of a lab report, a discussion of common writing mistakes that tutors have observed, a review of the rubric, and an agreement of the proposed structure of the visit.

PREPARATION OF WRITTEN MATERIALS: HANDOUTS, RUBRICS AND ASSIGNMENT NOTES

The written materials included the following: a grading rubric (Supporting File S1: Example grading rubric for the rough and final drafts of the lab report), lecture slides (Supporting File S2: Lecture slides- Components of a laboratory report), the Writing Center handout (Supporting File S3: Writing Center handout- guidance for visit to the writing center, and the Office Hours handout (Supporting File S4: Office Hours handout- guidance for office hours visit). Specifically, the Writing Center handout explained how to prepare for the visit to the writing center, provided talking points on common mistakes in traditional lab reports to discuss with their writing tutor, and asked students to write three concerns associated with their writing. The handout had a place where the student received a stamp from the tutor as evidence of their visit. The Office Hours handout detailed when and where my office hours were and required students to schedule a visit using Google calendar. It also contained a pre-assignment exercise in which students described three areas of strengths of their lab reports, three areas that they have noticed in which they are struggling, and listed questions that they could ask me during the meeting. The rough/final draft rubrics listed sub-scores for elements of the lab report such as the conventions in a traditional lab report with added guidance on the topics for background information in the introduction, quantitative analysis of the treatment groups in the results, and the rationale of the results and broader impacts in the discussion. The lecture slides outlined and explained the various components of a lab report.

IN-CLASS LECTURE SCRIPT

WEEK ONE

Many students did not have experience writing a lab report or using a substantive rubric guide for a writing assignment. Therefore, students received the rubric of the lab report and had a few minutes to review the document. In a 20 min lecture, I provided further explanation of the structure of a lab report. Many of the elements of the lab report that I discussed were echoed in the rubric. Students had time to ask questions about the rubric or components of the lab report.

WEEK TWO

I introduced the first assignment at the beginning of the laboratory class one week before the rough draft was due. I described the writing center and stated that its goal was to help students in the writing process and to provide low-stakes feedback prior to submission of a written assignment. While I was describing the writing center, the students received the Writing Center handout. I explained the tasks listed in the handout. I explained that the assignment would be evaluated based on the completion of the tasks listed in the Writing Center handout by the due date. I also offered helpful tips such as visiting the writing center's website to review the hours, location, and biographies of the tutors.

In the same class session, I asked the students to think of three concerns that they have regarding writing the rough draft of the lab report and then write these concerns on the Writing Center handout. I reviewed these concerns to ensure that a writing tutor could answer them. During the three-hour lab session, the students who wrote their three concerns received credit for completing this portion of the assignment (six points out of a possible 24 pts). The remaining tasks listed in the handout were completed outside of class. These tasks included the following: the responses to the questions they asked the writing tutor (three points); evidence of the visit to the writing center and completion of the tasks listed in the Writing Center handout (three points); and the marked-up copy of the draft that they edited with the tutor (12 pts). The due date of the assignment was the day before the due date of the rough draft to avoid last-minute visits to the writing center.

WEEK THREE

Prior to class, I graded and returned the rough drafts of the lab reports to the students. If the students did not receive full credit for a section, I described how to meet the requirements in the rubric line item e.g. "Add results in the abstract". At the beginning of the laboratory class, students received the Office Hours handout and I reviewed it in class. I also described what to expect during the office hours visit. I asked students to bring a copy of their rough draft, graded rubric, and a reflection describing three strengths of their lab report and three areas that they would like to strengthen.

I encouraged the completion of this assignment by reminding students that the assigned visits to the office hours were assessed by the completion of the three tasks. These tasks included the following: scheduling the visit to my office hours (four points); reviewing their rough draft and determining the strengths of the document and areas that they would like strengthen (four points); and visiting office hours to discuss the areas listed above in their rough draft (four points out of a possible 12 points). I reminded students that visiting office hours can increase their understanding of the course material. The due date for the assignment was the day before the submission of the final draft to curb last-minute visits.

TEACHING DISCUSSION

OBSERVATIONS

I was inspired to create this learning strategy after noticing the wide range of scientific writing skills from upper level Biology majors. The goal of this learning strategy was designed to provide guidance to students prior to the submission of a writing assignment. With the guidance of a substantive rubric, students first wrote a rough draft of a traditional lab report that contained the traditional conventions. The strategy included two instances of reflection of their scientific writing followed by low-stakes feedback of their report from a peer tutor and their instructor. I also wanted to create a learning environment that encouraged students to recognize areas of their scientific writing that they need to strengthen before seeking help from campus resources. I assigned two low-stakes assignments that were assessed based on the completion of tasks related to the utilization of office hours and visits to the writing center. These assignments provided an easy avenue to stimulate interpersonal skills between students and campus resources.

The above assignments also helped to balance the anxiety that some students experience in a high-stakes assignment. Overall, students in my single section of this course had higher grades than other sections. Although I have not tracked the outcomes of the students in my section of the course, I would be interested in studying the outcomes of students exposed to help seeking behavior early in their college careers.

REACTION FROM STUDENTS AND WRITING TUTORS

Before these assignments, many of the students had never visited the writing center and few came to my office hours. The students were open to the visits to office hours and the writing center because these assignments were graded based upon completion of the tasks. At the writing center, many students were concerned about the correct use of in-text citations and sentence structure of the reports. During the one-on-one office hours, I was able to get to know the students better by discussing what worked well in their rough draft grades as well as how they could edit their document to meet the rubric’s guidelines. Below are verbal comments from students regarding their visits to the writing center and office hours.

"This section feels more professional than other sections." - In regards to going to the writing center and office hours for help on lab reports

"My tutor was really nice. I'm thinking about being a writing tutor next year."

"I never thought about reading out loud as a way to proofread."- In response to learning a proofreading technique during an office hours visit.

The writing tutors and director of the writing center were at first apprehensive of mandatory visits to the writing center. This concern is widely shared among campus writing centers (7). However, the tutors mentioned that the students were kind and courteous. Some tutors commented that this assignment was essential in encouraging help-seeking behavior earlier in post-secondary education.

LIMITATIONS IN OTHER SETTINGS

Most students in our Introductory Biology course lived on campus, allowing easy implementation of these assignments. In contrast, this learning strategy could have constraints at institutions serving large populations of commuters or part-time students who may find it difficult to access writing center hours. This specific learning strategy may also be difficult for courses with large enrollments which may strain the availability of writing tutors and the instructor for one-on-one meetings during office hours.

POSSIBLE MODIFICATIONS

This learning strategy was completed in three weeks and I evaluated a rough draft of the lab reports. Some instructors may not find it necessary to use rough and final drafts of lab reports. Therefore, I suggest the following timeline. During week one, the instructor could deliver a lecture to introduce the format of a lab report the grading rubric. During week two, students could go to the writing center with their "rough" draft. Then the students would edit their document according to the feedback from the writing tutors. During week three, students could draft specific questions that they have regarding the lab report and/or rubric before the office hours visit. The students could submit the lab report by the end of week three.

Before going to the writing center, students could form small groups to discuss the challenges that they face with scientific writings. This activity would allow students to see that their peers also have concerns about scientific writing.

The structured visit to the writing center focused on receiving feedback in specific areas of scientific writing such as sentence structure; the inclusion of a testable hypothesis, summary and comparison of testable groups in the results; and a biological explanation of the results in the discussion that matches the testable hypothesis. I choose these topics because they were common mistakes that I saw in previous lab reports. These focus areas can be modified to fit the needs of the student population.

SUPPORTING MATERIALS

- S1. Scientific Writing - Grading Rubric. Example grading rubric for the rough and final drafts of the lab report.

- S2. Scientific Writing - Lecture slides. Lecture slides for the various components of a laboratory report.

- S3. Scientific Writing - Writing Center handout. Guidance for visit to the writing center.

- S4. Scientific Writing - Office Hours handout. Guidance for office hours visit.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the director of the SUNY-Oswego writing center, Steven Smith, and writing tutors for their guidance. I would like to thank the faculty in the Biological Sciences at SUNY-Oswego for help developing the grading rubric.

References

- American Association for the Advancement of Science. 2011. Vision and change in undergraduate biology education: A call to action.

- Gibbens BB, Gettle N, Thompson S, Muller K. 2015. Using Gamification to Teach Undergraduate Students about Scientific Writing. CourseSource. https://doi.org/10.24918/cs.2015.7.

- Fallahi CR, Wood RM, Austad CS, Fallahi H. 2006. A Program for Improving Undergraduate Psychology Students' Basic Writing Skills. Teach Psychol 33:171-175.

- Hood-DeGrenier, J.K. 2015. A Strategy for Teaching Undergraduates to Write Effective Scientific Results Sections. CourseSource. https://doi.org/10.24918/cs.2016.13.

- Salem L. 2016. Decisions...Desisions: Who Chooses to Use the Writing Center? Writ Cent J 35:147-171.

- Pfrenger W, Blasiman RN, Winter J. 2017. "At First It Was Annoying": Results from Requiring Writers in Developmental Courses to Visit the Writing Center. Prax A Writ Cent J 15:22-35.

- Wells J. 2016. Why We Resist "Leading the Horse": Required Tutoring, RAD Research, and Our Writing Center Ideals. Writ Cent J 35:87-114.

- Kuh GD. 2008. High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter. AAC&U.

- Mineo L. 2017. Professors examine the realities of office hours - Harvard Gazette. Harvard Gaz. Cambridge, MA.

- Karaivanova K. 2016. The effects of encouraging student-faculty interaction on academic success, identity development, and student retention in the first year of college. University of New Hampshire.

- Guerrero M, Rod AB. 2013. Engaging in Office Hours: A Study of Student-Faculty Interaction and Academic Performance. J Polit Sci Educ 9:403-416.

- Gooblar D. 2015. Make Your Office Hours a Requirement. Chron Vitae.

- Jackson LE, Knupsky A. 2015. "Weaning off of Email": Encouraging Students to Use Office Hours over Email to Contact Professors. Coll Teach 63:183-184.

Article Files

Login to access supporting documents

Visits to the writing center and office hours provide students structured reflection and low-stakes feedback on scientific writi(PDF | 128 KB)

S1. Scientific Writing Grading Rubric .docx(DOCX | 23 KB)

S2. Scientific Writing Lecture slides.pptx(PPTX | 43 KB)

S3. Scientific Writing Writing Center handout.docx(DOCX | 15 KB)

S4. Scientific Writing Office Hours handout.docx(DOCX | 15 KB)

- License terms

Comments

Comments

There are no comments on this resource.