Starting Conversations About Discrimination Against Women in STEM

Editor: Tracie Addy

Published online:

Abstract

Many scientists know about — and experience — discrimination against women. In this professional development lesson, graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, faculty, and other career scientists brainstorm ways to intervene and support women when they experience discrimination. Participants divide into groups, and each group discusses one of four case studies that highlight different kinds of discrimination, namely microaggressions that are gendered and intersectional, trolling, and sexual harassment. Within the small groups, individuals discuss the case study and then brainstorm ways to bring the discrimination to the perpetrator's attention and ways to dismantle sexism within each individual's environment. Then, the whole group reconvenes to discuss each case study in a way that emphasizes empowerment. Dismantling sexism seems overwhelming, but by the end of the workshop each participant can leave thinking about actions to take appropriate to their identities and career stages. Future workshops are necessary to address gender discrimination more broadly — especially as it pertains to particularly marginalized identities such as transwomen of color — and for developing deeper action plans.

Primary image: This image represents women in science — we are here, but we often feel trapped.

Citation

Price RM. 2020. Starting conversations about discrimination against women in STEM. CourseSource. https://doi.org/10.24918/cs.2020.29

Lesson Learning Goals

Discussion attendees will:

- recognize discrimination against women, including microaggressions, trolling, sexual harassment, and the compounded discrimination that occurs when multiple identities intersect.

- practice responding to different kinds of gender discrimination by considering women featured in case studies, the people conducting the discrimination, and the institutional structures that allowed the discrimination to occur.

- identify steps they will take in the next three months to address gender discrimination.

Lesson Learning Objectives

After the discussion, each attendee will be able to:

- identify common forms of discrimination that women in academic STEM positions experience.

- begin supporting women while and after they experience discrimination.

- implement institutional change at a scale that is appropriate for them.

Article Context

Course

Article Type

Course Level

Bloom's Cognitive Level

Vision and Change Core Competencies

Class Type

Class Size

Audience

Lesson Length

Pedagogical Approaches

Principles of How People Learn

Assessment Type

INTRODUCTION

Discrimination is everywhere, and as educators we must do our utmost to set up environments that are as free from it as possible. This lesson addresses sexism, a specific type of discrimination based on gender. Awareness about the discrimination that women experience in the United States has increased greatly in the last few years, with extensive attention to sexual harassment and assault through the #MeToo movement (1,2). Within the sciences, this awareness resulted in a 2018 report by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) entitled Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (3), as well as their subsequent project on Addressing the Underrepresentation of Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine.

The NASEM report is an excellent introduction to and summary of the literature about discrimination against women (3), analyzing specific sexist behaviors and systems that emerge from bias. This lesson draws on some of the report’s main themes, and I recommend that anyone who wants a data-driven history of discrimination against women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) read it; one caveat is that it prioritizes the experiences of cis-gendered women, rather than other minoritized genders, such as people who are transgender or nonbinary. The report emphasizes that we are working in a culture in which sexual assault is the tip of an iceberg of pervasive forms of discrimination that undergird and create an environment that enables more egregious harm. Changing STEM culture to be more welcoming to women means recognizing and confronting different forms of discrimination in ways appropriate to one’s identity in the academy (3).

The metaphor of an iceberg (3) explains the broad definition of gender discrimination. The visible part of the iceberg — sexual assault — receives more public attention than a host of inappropriate behaviors below the waterline that reflect a misogynistic culture. One purpose of this workshop is for participants to begin discussing examples of acts, such as microaggressions (4), that pave the way for sexual harassment, trolling, and sexual assault, and other important factors to consider, such as the intersectional effects of gender and race.

Microaggressions and intersectionality are two terms essential to understanding many of the arguments made in the NASEM report (3) and discussed in this article. Microaggressions, addressed extensively in Derald Wing Sue's Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation (4) and as stereotypes in the Claude Steele’s groundbreaking and accessible book Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do (5), are, to oversimplify, small comments or actions that reflect stereotypes. As the NASEM report observes (3), the prefix micro is misleading, because microaggressions can be quite damaging. To draw an example from my personal experience, when I was a graduate student, a professor’s first reaction to finding out that I had received a major grant was to say “Why didn’t [male graduate student] get that grant?” This comment, in the context of other experiences, made me feel that the grantors had made a mistake in offering me an award. The accumulation of microaggressions over time is especially damaging (4,5).

Intersectionality, a term coined by Black feminist legal scholar Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw, initially described the unique experiences of being both a gender and racial minority — the type of discrimination, and amount of it, differ from the experiences of carrying only one of these labels (6). In other words, a Black woman’s experience of discrimination is distinct from a white woman’s experiences and distinct from a Black man’s (7). Moreover, anti-discriminatory work historically focused on gender or race, but not the combined effects of both (6,7). As such, white feminists (such as me) must take great care to ensure that their work to end gender discrimination includes all races and genders. Since Crenshaw coined the term, others have broadened the definition of intersectionality to include any combination of marginalized identities (e.g., 6).

Beginning in 2016, The Gordon Research Conferences® (GRC) have joined the effort to make STEM more inclusive to women by adding a GRC Power HourTM to their conferences. This session is “designed to address challenges women face in science and issues of diversity and inclusion. The program supports the professional growth of all members of our communities by providing an open forum for discussion and mentoring.” A key element in the design of the GRC Power HourTM is its flexibility, in that the conference chairs select a woman from their field to design a session appropriate for that particular discipline and community. Someone from the discipline is better able to identify the needs of their particular community, as well as to tailor the discussion to that community’s strengths (9). The GRC Power HourTM that I designed for the 2019 Undergraduate Biology Education Research GRC used case studies, because biology education researchers often work with case studies (9) and because they are an effective strategy for training about discrimination (10). I chose four examples that highlight different forms of discrimination against women, with differing levels of severity: microaggressions, Internet trolling, sexual harassment, and microaggressions related to intersectional identities. Of course, there are many more forms of gender discrimination than what are highlighted in these four cases, but a one-hour discussion can only scratch the surface.

Discussing the case studies gives participants the chance to practice different types of interventions on behalf of women. Examining case studies achieves the personal connection that story telling fosters, but it also retains some distance because the people are not physically present, making it easier to comment on and try different strategies of support. Note, however, that despite their distance, some of the case studies may — and probably will — closely align with the experiences of some participants.

All too often discussions about discrimination leave people feeling dispirited, which may happen to some participants. Some scientists have spent entire careers working to include women in STEM research and STEM careers, and the current national climate emphasizes how much change is still necessary (3). However, this discussion generates strategies that empower people to effect positive change. My hope is that participants leave empowered to take actions appropriate to their identities.

Intended Audience

I developed this discussion for graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, faculty, staff, and administrators attending the 2019 Undergraduate Biology Education Research GRC. That said, I believe the workshop is appropriate for multiple STEM audiences, not just biological ones.

Required Learning Time

This discussion lasts one hour. Because gender discrimination is a topic about which people are passionate, I included in the handout a number of additional resources that attendees could pursue afterwards if they desired.

Prerequisite Student Knowledge

This discussion introduced attendees to ways to change a culture that is hostile to women. Because this workshop was developed for biology education researchers, I assumed that members of the audience would be familiar with active-learning practices, and that they would be able to facilitate group dynamics that include: reading and answering questions before participating in small group discussion, allowing everyone in the group time to speak, and forming small groups of an appropriate size. With other audiences, I would spend time understanding how familiar people are with active learning and facilitating group work in equitable ways. I also assumed that some audience members had experiences similar to those presented in the case studies, others would not have experienced any of them, and that everyone present wanted to decrease discrimination against women. It may be helpful to share these assumptions at the beginning of the workshop, for example by saying “Please be prepared for potentially difficult conversations. Some of you may have experienced situations like the ones we are about to discuss. Feel free to take a break or leave if the conversation is not working for you.”

Prerequisite Teacher Knowledge

Facilitators should be prepared for attendees’ strong emotions, as well as participants with different personal experiences with gender discrimination. Participants could include people who have been working to achieve gender equity in their fields for decades, as well as those who have spent decades unaware of the discrimination their colleagues have been experiencing. Some of the case studies may resonate so deeply with participants that they feel quite emotional. It is essential for the attendees to listen to and acknowledge experiences of audience members who share stories of discrimination.

The facilitator should acknowledge and address the tension between marginalized genders and men — the gender that traditionally holds power. Some men who acknowledge the need for conversations to occur among marginalized genders may feel that it is inappropriate for them to attend. However, this conversation is intended to include all genders to explore common discriminatory power dynamics and to brainstorm how to change the power dynamics to be more equitable. An essential part of progress is listening to peoples’ experiences, and this conversation attempts to create a listening space.

This lesson incorporates breathing exercises to help ease attendees’ tension. If the facilitator chooses to use these exercises, they must know how to lead a community in deep breathing.

Whenever a group of people engages in a difficult conversation, feelings can be hurt. Ouch-oops is a technique that a facilitator can use to encourage attendees to surface when their feelings are hurt — and it must be acknowledged that statements that hurt feelings can be microaggressions and are distressing (11). I have used this method when I have taught this lesson, and it has allowed the group to resolve tensions that would have otherwise been unaddressed. Implementation of the technique begins when someone says “ouch.” This statement introduces an opportunity for feedback, in which the unintended aggressor can hear why what they said was offensive. The aggressor must agree to listen to the feedback and accept the other person’s experience. For example, a reviewer of an earlier version of this manuscript correctly pointed out to me that the case studies in this lesson do not address the experiences of trans folx. In my response, I acknowledged the feedback and thanked the reviewer for providing it. I also edited the manuscript to address this limitation more clearly. In the Teaching Discussion below, I suggest including a case study about trans folx in the future. This same kind of acknowledgment can exist aloud in the workshop itself. I could imagine a participant in a future workshop asking about the experiences of transwomen. I can also imagine a participant asking why three of the four cases studies include white-presenting women, rather than women of color — another limitation that I now regret. A participant may have pointed out my oversight by stating “ouch.” I would listen to the feedback, thank them for it, accept my oversight as a microaggression, acknowledge that my exclusion had a negative impact, and offer a change to implement in the future. I would say “oops” as a way to highlight the fact that I made a mistake and my intention to correct it moving forward (11).

Instructors should know how to prioritize input and viewpoints from those who are marginalized. A consequence of bringing the experiences of people who are marginalized into the center of a conversation is that some people are resistant to this change in perspective and will be angry about it. They may even express hostility (12). The facilitator must be able to redirect this hostility and maintain the focus of the discussion on supporting and centering the experiences of people with marginalized genders (12).

Finally, the facilitator should be familiar with each of the four case studies, and the key concepts they explore: microaggressions, Internet trolling, sexual harassment, and intersectionality. These four concepts are discussed in more detail below (See Lesson Plan) and in the references that accompany the case studies (provided in Supporting File S1. Discrimination Against Women –Worksheet and Case Studies). Briefly, microaggressions are discriminatory statements or actions that, on their own, are relatively minor. However, when they are repeated continually, they contribute to a hostile environment (13). A common microaggression about race in the United States occurs when white people ask people of color “where are you really from?” (14). A microaggression that women in STEM experience is being thought of as aggressive when asking a question in a research seminar. Internet trolling occurs when someone is harassed through social media, and women who are trolled are often subject to threats of violence, including rape (15). The NASEM report applies a broad definition of sexual harassment that includes any harmful behavior based on gender (3). Harassment of a sexual nature, in addition to gender-based harassment that is not sexual, continues to be common in STEM fields (3). Intersectionality refers to the multiplicative effect of more than one marginalized identity (e.g., 6), such as the double bind (16) that women of color experience — a multiplicative effect of discrimination both from gender and race (6,7).

This assemblage of qualifications for the facilitator is a tall order, and, although I developed the lesson, it pushes the bounds of my expertise. For some workshops, the best solution may be for two facilitators to lead the session — one person representing the audience members’ field of expertise, and a second person with training about gender discrimination and the ability to support participants who might become upset during the workshop. The combination of disciplinary expert and counselor is an especially powerful one. Workshops always occur in a community (17), and the disciplinary expert brings knowledge of what that community knows and how it behaves. I developed this lesson to be delivered on my own because The Gordon Research Conferences® wanted a member of the conference community (here, the biology education community) to lead the Power HourTM.

SCIENTIFIC TEACHING THEMES

Active Learning

The active learning components of this lesson include individual free writes, a case study to read and answer in a think-small group-share, and whole group discussion facilitated by a combination of the facilitator and representatives from the small groups. In this case, having a discussion within a small group works better than discussing in a pair, so that more people can brainstorm ideas on how to address the discrimination outlined in each case study; sometimes, it can take time to start brainstorming solutions and actionable steps to confront discrimination against women. These activities are all described in the lesson worksheet that is distributed to each participant.

The activity was originally intended to be a jigsaw (18), and that format would work with a small audience of up to 12, with only one small group discussing each case study. However, when I have led the discussion, I have had groups of greater than 20 and up to 80, and the attendees have been eager to talk with the whole audience. Allowing more time for the whole group discussion was a beneficial and necessary change to accommodate the larger number of participants.

Assessment

While small groups discuss the case study to which they’ve been assigned, the facilitator circulates through the room listening to different conversations. They note the ideas that are being discussed and that need to be surfaced during the whole group discussion. The facilitator is also redirecting the conversation as necessary and telling the small groups how much more time they have to discuss the case.

Aspects of the whole group discussion provide formative assessment for the facilitator. The details that people report out may differ slightly from the nature of the case studies themselves; this disconnect is quite helpful, because it tells the facilitator what about each case resonated with different groups, offering information about how to modify and highlight aspects of each case for different audiences. It is also informative to hear when a member of the audience — or the facilitator — says “ouch,” using the method described above in Prerequisite Teacher Knowledge. A facilitator learns a great deal about how to improve the discussion by tracking what kinds of comments motivate someone to say “ouch,” and often this feedback can lead to more clarity. For example, someone told me “ouch” when I initially asked people to self-identify whether they would be appropriate representatives for their group. A white man said “ouch” in jest to indicate that he felt it would be inappropriate for him to speak. We discussed his point as a group, acknowledged that there are times when a white man can speak for a group, and times when it is inappropriate. We decided to have each small group decide collectively who could represent the identities and content that their group wanted to project. This strategy of letting the group decide on a representative was much more inclusive than having an individual decide on their own to speak for the group.

Inclusive Teaching

Each attendee has a worksheet (Supporting File S1. Discrimination Against Women – Worksheet and Case Studies) to help structure their free writes and to follow the conversation. Everyone in the discussion reads a case study and reflects on it on their own. Then, participants discuss their case study in small groups, which allows participants to reflect on their own social identities and experiences, as well as those of others.

Each group works together to choose someone who can share details of their discussion with the whole audience. If time allows, there are also reflection questions at the end of the discussion that each individual can answer.

LESSON PLAN

The lesson is a structured, hour-long conversation. As with any discussion, the facilitator may decide to shrink and stretch different aspects of the lesson plan based on how their particular audience processes the material. The format could be changed to a jigsaw, especially with a group of 12-16 people. Make sure to have enough handouts — or a URL to distribute — for all participants. I typically have handouts available on both paper and through a freely accessible Google doc.

Introduction

Spend the first five minutes of the discussion introducing ground rules and the topic, and offer that some people may need to leave or take a break, given the weightiness of the topic. It is crucial to emphasize self-care whenever leading a discussion like this. If the discussion is being held at a conference, this is a good time to tie the discussion to themes from other presentations. I also go over the learning goals and objectives, which are all included in the worksheet (S1. Discrimination Against Women – Worksheet and Case Studies). Because one of the learning objectives asks participants to identify something that they can do in the near future to address gender discrimination, it is helpful to explain that actions depend on the power they have, and power is determined by a suite of identities. People are comfortable taking different actions depending on their career stage, gender, race, ability, etc. Facilitators should acknowledge tension around the topic and indicate that people make mistakes. What's critical here is learning how to listen to women about their experiences of marginalization. I found it helpful to share that I have made mistakes when talking to people about gender and racial justice, that I am learning from my mistakes, especially given my position and privilege as a white woman (12). This work is humbling and dynamic, and I am constantly learning. Alas, learning requires mistakes (19). This is also the time for the facilitator to introduce the "ouch" technique. Tell the participants that "If your feelings are hurt, please say 'ouch.'" Then, if someone says "ouch" during the discussion, please stop the discussion and address the concern with "oops."

I work through an example of this below in Teaching Discussion: Challenges.

I also ask if participants would like to do breathing exercises, making it clear that doing them is optional. Thus far, they have welcomed breathing exercises, but I would leave them out if a marked majority of the audience does not want them.

At the end of the introduction, assign attendees to different small groups. Some small groups may wish to leave the room to have more space and so that their own discussion does not overlap with that of other groups. The ideal group size is 3-5 people. To save time, I divide the room into four sections, with small groups in each section working on the same case study.

Case Studies

There are four case studies that highlight four different forms of discrimination against women: microaggressions, trolling, sexual harassment, and intersectional microaggressions. I describe them briefly here, and all cases are presented in S1. Discrimination Against Women – Worksheet and Case Studies.

Case Study: Microaggressions

The case study about microaggressions discusses a fictional incident in which a white woman was perceived as aggressive because she asked questions during seminars. She resolved the conflict with the colleague who labeled her as aggressive. However, when she shared the experience with the male chair of a department with several female assistant professors, he became angry and declared that the women in his department needed no additional support.

Case Study: Trolling

The case study about trolling discusses Dr. Katie Bouman, the lead scientist (and white-presenting woman) in a large team that allowed the world to see a black hole for the first time. Dr. Bouman's credentials were undermined by media, and she was trolled by people unable to accepts that a woman could lead such a large and successful collaboration (20). A more common kind of Internet trolling occurs on websites such as ratemyprofessor.com (21).

Case Study: Sexual Harassment

The case study about sexual harassment is a blog post by Dr. Rebecca Rogers Ackerman (a white-presenting woman) and published on Tenure She Wrote in 2016. The blog details harassment and assault that Dr. Ackerman has experienced throughout her career and the desire to flee from each situation. As her career advanced, however, she saw the same perpetrators continue to harass young, female graduate students. The blog ends powerfully with the statement "I have always been open with my students about what has happened to me, so that they might be more aware of these issues, and learn from them. Now I am ready to be open with everyone...I am done keeping this under wraps. Done." Notably, the blog was published the same week that Science published an article about a renowned anthropologist accused of sexual misconduct involving a number of female subordinates (22). The anthropologist resigned from his high profile position shortly after the Science article documenting the accusations was published (23). Ackermann's blog precedes and presages the start of the #MeToo and #MeTooSTEM movements (2).

Case Study: Intersectionality

The case study about intersectionality quotes from a scholarly article by Dr. Chavella T. Pittman about interactions between women of color and their white male students (24). The article analyzes the transcripts of interviews with 17 female professors of color who teach at predominately white institutions. The case study pulls quotations from two of the professors who recall times when white male students undermined their expertise in front of an entire class. In both cases, the professors felt that the rudeness they experienced was the result of the students' disrespect of the combination of both their gender and race (24). The students claimed that their own expertise was superior to that of their professors. These particular examples are microaggressions. Each of these experiences on its own would be irritating. It is the constant display of this disrespect, combined with constant devaluation in other contexts, that accumulate to build a hostile environment.

Teaching the case studies

Participants have 30 minutes to complete individual work and a small group discussion on the case study to which they have been assigned. Each participant reads the case study and answers the questions on the worksheet on their own. After that, each small group can discuss the details of their particular case. As stated in the worksheet (S1. Discrimination Against Women – Worksheet and Case Studies), the questions at the end of each case ask participants to:

- Identify the gender discrimination in the case study.

- Brainstorm about ways to bring the bias to the perpetrators' attention.

- Compare the advantages and disadvantages of an environment that allows people to bring bias to the perpetrators' attention.

- Identify actions that people can take — appropriate to their personalities and stages in their careers — in the next three months to confront sexism in their environments.

The case studies are written in such a way that the discrimination in them is obvious, but it is much more challenging for participants to address the other questions on the worksheet. Some people may not know ways to expose discriminatory actions, and as the first case study illustrates, even calling attention to microaggressions can result in anger being directed against the person who calls attention to a relatively minor form of discrimination. In a day and age when women are openly ridiculed and threatened as a result of making serious allegations of sexual assault against some of the most powerful men in the world (25,26), the risks for women to self-advocate must be acknowledged and considered.

I begin circulating among the participants as soon as the individual work begins. My pace is quite slow at the beginning to allow enough time for everyone to read the case studies. I encourage participants to write down their answers to the questions, especially if they finish reading before their groupmates. However, people are eager to talk about what they read, and typically not everyone will write down their answers.

Most groups are conversing within 10 minutes, but it is still helpful to announce when 10 minutes have passed and that all groups should be discussing their case studies at this point. I continue circulating among the groups, now paying attention to the ideas that surface and making sure that participants are brainstorming about actions they could take to mitigate comparable examples of discrimination. I also tell the groups when they have only five minutes left before it is time to reconvene into one large audience. This is a good time to remind the groups to choose a spokesperson who can report out to the whole audience. It is helpful to remember that it takes time for the groups to reassemble into one audience.

This part of the lesson concludes with the first breathing exercise, again reminding participants to follow along only if they so desire. I ask people to inhale for a count to four, and to exhale for a count to four, and to do this twice. Rather than counting aloud, I raise my hands slowly to indicate the inhale, and then lower them slowly to exhale. That allows me to participate in the deep breathing, too.

Whole group discussion

Because time has always limited me from having representatives for all groups report out, I prioritize hearing from the groups that discussed microaggressions and intersectionality. I focus on these two cases because they represent the easier ways for people to intervene to change an underlying culture that allows the more egregious forms of discrimination to occur (3, https://tenureshewrote.wordpress.com/2016/02/09/it-is-time-my-personal-journey-from-harassee-to-guardian/#more-2567). It is also essential to address intersectionality because working against gender discrimination has often centered women with majority identities, i.e., cisgendered, white women (3). Progress relies on understanding the unique perspectives of women that carry other identities.

Before the reports, I remind participants that there is space on their handout to take notes about each case study. Then, I ask the reporters to briefly summarize their case study in one minute, and then to share their ideas about the actions they could take. When a group finishes reporting, I briefly summarize what I learned from the discussion for the audience, emphasizing the actions that could be taken, and reminding participants again that their actions depend on what they can do at this point in their lives.

Participants come up with a number of excellent small steps to take that address discrimination against women in their work environments. These include:

- listening to colleagues' experiences and being open to hearing the discrimination they have experienced even if you would not process a similar experience as discrimination;

- waiting to ask a question after a seminar until a female colleague has asked one;

- using inclusive teaching practices in our classrooms (27);

- asking people from marginalized identities, including but not limited to women, people of color, and people of different ability, how a department can support them; then acting on their requests;

- valuing work related to increasing diversity in hiring, promotion, and tenure cases;

- lunch time talks to discuss the National Academies report on sexual harassment (3);

- organizing a women's group during which people can gather to discuss whatever issues and concerns emerge;

- inviting speakers/workshop presenters to their departments who can lead sessions about discrimination against women or related concepts, including deeper exposure to intersectionality; and

- working with departmental and institutional leadership to make systemic changes that support women and other marginalized people.

Together, these small steps can accumulate to dismantle sexism.

The whole group discussion concludes with another breathing exercise, this one based on a yoga technique called kapalabhati breathing. Some people are not comfortable meditating in public, so it is crucial to invite people to participate if they would like to, but also to emphasize that it is okay not to participate. I model the breathing technique for the participants, and then we all do it together. The technique, as adapted here, requires a deep inhale, and then a series of rapid exhales, using a contraction of the abdomen to push air out. We do five of these rapid exhales, and go through two cycles of this breathing exercise. I find this breathing exercise to be quite energetic in this context. The combination of focusing on actionable steps and energetic breathing helps the lesson end on a positive note, despite the difficult topic.

Wrap up

If time allows, the facilitator can ask the participants to complete the reflection at the end of the worksheet. This provides an opportunity for people to write down any discrimination they have experienced and/or witnessed, and to acknowledge the ideas and emotions that emerged for them during the discussion.

I conclude the lesson by thanking the participants, by introducing them to the additional resources at the end of their handout, and by introducing an Appendix (S2. Discrimination Against Women – Worksheet Appendix). The additional sources include information about organizations like Below the Waterline whose mission is to end sexual harassment; the collection of essays Presumed Incompetent: The Intersections of Race and Class for Women in Academia (28); databases that track incidents of sexual harassment in the academy (https://geocognitionresearchlaboratory.com/2018/08/20/the-academic-sexual-misconduct-database/, https://theprofessorisin.com/2017/12/01/a-crowdsourced-survey-of-sexual-harassment-in-the-academy/, 28); and resources about gender bias in student evaluations (21,30).

The documents in the Appendix (S2. Discrimination Against Women – Worksheet Appendix) highlight recent actions that demonstrate that our community is moving in a more equitable direction. The intent, again, is to reinforce that we can take steps to minimize and mitigate the negative effects of discrimination against women. Thus far, the Appendix used includes an excerpt from an article in the journal Human Geography that calls out an academic culture that rewards perpetrators of sexual harassment, followed by a press release by the National Academies about their recently approved bylaw that their council may rescind the membership of proven perpetrators of sexual harassment.

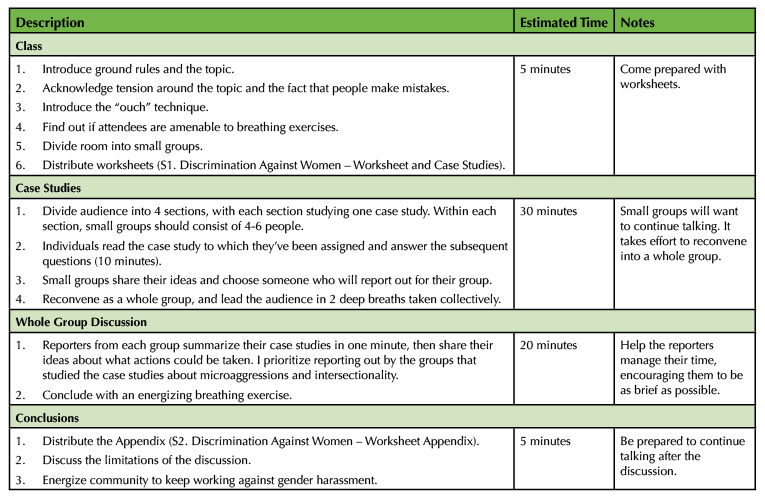

Table 1. Discrimination against women lesson plan timeline.

TEACHING DISCUSSION

Context of the conference

A key element to the success of this discussion is placing it into the context in which it is delivered. I have presented it to communities of biology education researchers in different settings. This Teaching Discussion is about the time I presented this lesson at a Gordon Research Conference®. At the conference, I announced that people of all genders were welcome to attend and participate, and that working against discrimination of women requires work from people of all genders. Some men told me they would not have attended the discussion if I had not made that announcement. Another way in which I contextualized the discussion into the place of this conference was by referring to other talks on complementary topics. Because the discussion was at the beginning of the conference, I continued discussing the material with attendees for the rest of the conference. The fact that so many people came up to me with follow up questions and comments meant that it was particularly helpful to hold the discussion at the beginning of the conference, and that the opportunity to continue conversation afterwards was valuable.

Reactions to the Lesson

Conference attendees were at many different stages of their careers, ranging from graduate students to retired academics. Consequently, attendees had a range of histories both in terms of experiencing gender discrimination and in fighting gender discrimination. For example, some attendees were new to the ideas of microaggressions and intersectionality, and others held a deep-seated sense of frustration over the lack of change. This particular lesson is introductory in scope, and so may not be appropriate for scholars more experienced in advocating to fight discrimination against women.

For some attendees, the breathing exercises helped dissipate feelings like frustration, helplessness, and anger. My impression was that they replaced these feelings with ones of empowerment.

When representatives of the small groups reported on their discussions to the whole audience, they emphasized different aspects of the cases, indicating that different details resonate with different people. In fact, some people misremembered details about the case studies. In the case study about microaggression, for example, one reporter slightly modified the way the chair responded to Dr. Cohen's conversation with her colleague who had commented on her aggressiveness in asking questions during a seminar. In the original case, the chair was mad that Dr. Cohen brought up the microaggression at all; the reporter, however, shared that the chair was mad because he thought it was his job to talk to the colleague. The differences between these two versions of the case study are not essential, and it is best for the facilitator not to point them out. I mention them here to help the facilitator be aware that attendees will reinterpret the case studies in ways that are meaningful to them, and that help them process the discrimination they have witnessed and/or experienced.

Challenges

When I initially wrote this lesson, I had intended for it to be a jigsaw (18), so that all attendees could learn about all four case studies. In practice, however, I have found two barriers to the jigsaw. One was the room layout — the participants were arranged in stadium seating, so it was difficult to form the small expert groups, and it would have been even more challenging to redistribute into jigsaw groups. Also, the discussions occurring among the groups who read the same case study (the expert groups in a traditional jigsaw, 17) were so rich and engrossing, that I changed the format. I imagine that a jigsaw would still work for a smaller number of attendees if the room layout were conducive to forming and reforming small groups.

The biggest challenges in the lesson are, of course, around the difficult content. As is common in discussions around race (12,31), some participants denied that race contributed to the experiences of the female faculty of color in the case study about intersectionality — a case study whose text comes from a peer-reviewed, social science study about the experiences of female faculty of color. I did not hear these denials directly, but instead heard about them from other participants after the discussion was over. Had I heard them, I would have said "ouch", using the technique described above (Scientific Teaching Themes: Assessment). I then would have encouraged people to listen to the experiences documented in the case study. The goal of examining this particular case study is not to decide whether the interviewers are telling the truth; instead, the goal is to hear about the experiences and perceptions of female faculty of color. Anti-racist work requires that white people listen (12).

One participant did say "ouch" during part of our whole group discussion, and this provided an excellent opportunity to dissipate tension, improve the discussion, and model how to use "ouch" for the whole audience. We had just reconvened as a whole group after the small group discussions when I asked people to volunteer to report out for their groups, and to ask themselves if they would be an appropriate identity to represent the group. The "ouch" was a tongue-in-cheek moment (as clarified to me afterward) meant to bring up the question of whether men could be reporters for their group. I mentioned that there are times when I do not mind men speaking on my behalf, and that there are times when I feel it is inappropriate. To address the concern that was raised, I asked the small groups to have a quick discussion to decide who should represent their group. This approach was more appropriate, because it empowered each small group to choose its voice, rather than asking individuals to evaluate independently whether they should assume that responsibility. I have incorporated this improvement into the lesson plan.

The quality of anti-harassment training

A number of variables affect how well anti-harassment workshops work (32). For example, the gender of the facilitator and the motivation for participants to attend both contribute to a workshop's success, as does the environment in which attendees work (32). Moreover, the literature assessing the efficacy of this kind of professional development focuses on workshops that address the tip of the iceberg — sexual assault and misconduct, rather than professional development focused on the microaggressions that are pervasive in a misogynistic culture.

Even with these caveats in mind, this particular lesson draws on best practices. The participants choose to attend, suggesting that their motivation for coming is high (17), which tends to lead to higher incidences of positive change. The training is contextualized by the discipline of biology education, which offers a meaningful connection and relevance to the people in the case studies (10), instead of occurring in a vacuum (17,33). It occurred during a conference, so participants could continue talking for days after the workshop, ensuring a longer engagement with the materials (17). By focusing on case studies that describe women's emotional experiences, the training focused on an ethical, rather than legal, viewpoint (17), and builds skills as participants consider what they would say in different circumstances (17). Clear learning objectives indicate the behaviors that the workshop aims to nudge (10). Participants practice different interventions in small groups, so feedback is built into the experience (10).

Future considerations

Without an extensive research design, it is difficult to determine how successful this one-hour workshop is. It is unreasonable to expect that it does more than scratch the surface (32,34), although short trainings that use case studies can result in the ability to recognize sexual harassment (35). The learning objectives stipulated here require practice and cannot be measured by surveying participants' experiences immediately following the workshop (17). Effecting change requires time and practice within a supportive community (17,34). Future research on the efficacy of this or a comparable workshop would be welcome (10,33), such as a pre-post comparison of the ability to recognize different forms of discrimination (35), including microaggressions.

This particular lesson is introductory, lasts only an hour, and was tasked by The Gordon Research Conferences® to address discrimination of women. Due to these constraints, there are big gaps in the material that is covered. For example, there is a difference between gender discrimination and discrimination against women. With respect to gender, systems are in place to favor the success of men. However, the discrimination experienced by cisgendered women, transgendered women and men, and non-binary people all fall under the category of gender discrimination (3). The case studies presented here do not explore these different kinds of gender discrimination, and they center the experiences of cisgendered women. In the future, I would add a case study about the experiences of transgendered women in STEM fields and better represent the experiences of women of color. Of course, a single case study cannot address the experiences of an entire demographic, and an additional case study would be as introductory as those that I have included.

Someone — or a team — who chooses to teach this lesson must use the proper care and attention to hurt feelings. Teaching about discrimination can hurt feelings. For the facilitator, delivering the lesson is also unavoidably connected to their own identity, which affects how the participants perceive their facility with the material. Moreover, the facilitator will make mistakes. These challenges need to be recognized. We can prepare for them, and with practice, humble listening, and learning, make fewer mistakes.

SUPPORTING MATERIALS

- S1. Discrimination Against Women – Worksheet and Case Studies

- S2. Discrimination Against Women – Worksheet Appendix

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank the Gordon Research Conferences and the leadership team for the 2019 Undergraduate Biology Education Research GRC, specifically José Herrera, Debra Pires, Erin L. Dolan, and Stacey Kiser, for the opportunity to develop this lesson. This GRC was supported in part by funding from the HHMI, the National Institute of General Medicine Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number 1R13GM134534-01, and the NSF Division of Undergraduate Education Award 1922648. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the HHMI, NSF, or NIH.

I thank Kristin Gustafson for teaching me the "ouch" technique to label and address concerns that discussion participants raise. Lauren F. Lichty offered suggestions for how to couch difficult conversations, and Eva Y. Ma offered editorial advice. Chavella T. Pittman gave permission to use excerpts of "Race and Gender Oppression in the Classroom: The Experiences of Women Faculty of Color with White Male Students" from Teaching Sociology as a case study. GRC and the University of Washington Bothell, School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences IAS provided funding for me to attend the GRC conference. I consulted with University of Washington Title IX Coordinator Valery Richardson and University of Washington Bothell Violence Prevention & Advocacy Program Manager Elizabeth Wilmerding while preparing this manuscript. Finally, I thank CourseSource editors Michelle K. Smith and Tracie M. Addy and anonymous reviewers.

References

- Mansfield B, Lave R, McSweeney K, Bonds A, Cockburn J, Domosh M, Hamilton T, Hawkins R, Hessl A, Munroe D, Ojeda D, Radel C. 2019. It's time to recognize how men's careers benefit from sexually harassing women in academia. Human Geography 12:82-87.

- Mendes K, Ringrose J, Keller J. 2018. #MeToo and the promise and pitfalls of challenging rape culture through digital feminist activism. European Journal of Women's Studies 25:236-246. doi:10.1177/1350506818765318

- Committee on the Impacts of Sexual Harassment in Academia, Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Policy and Global Affairs, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

- Sue DW. 2010. Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

- Steele C. 2010. Whistling Vivaldi: and other clues to how stereotypes affect us. W.W. Norton & Company, New York.

- Crenshaw KW. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 139-167.

- Davis K. 2008. Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful. Feminist Theory 9:67-85. doi:10.1177/1464700108086364

- Museus SD, Griffin KA. 2011. Mapping the Margins in Higher Education: On the Promise of Intersectionality Frameworks in Research and Discourse. New Directions for Institutional Research 151:5-13. doi:10.1002/ir.395

- Perry EL, Kulik CT, Field MP. 2009. Sexual harassment training: Recommendations to address gaps between the practitioner and research literatures. Human Resource Management 48:817-837. doi:10.1002/hrm.20316

- Medeiros K, Griffith J. 2019. #Ustoo: How I-O psychologists can extend the conversation on sexual harassment and sexual assault through workplace training. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 12:1-19. doi:10.1017/iop.2018.155

- Aguilar LC. 2006. Ouch! That Stereotype Hurts: Communicating Respectfully in a Diverse World. The Brandt Company.

- DiAngelo R. 2018. White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Beacon Press, Boston.

- Harrison C, Tanner KD. 2018. Language Matters: Considering Microaggressions in Science. CBE – Life Sciences Education 17:fe4. doi:10.1187/cbe.18-01-0011

- Cheryan S, Monin B. 2005. Where are you really from?: Asian Americans and identity denial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89:717-730. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.717

- Sarkeesian A. Anita Sarkeesian at TEDxWomen 2012 - YouTube. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-wKBdMu6dD4

- Malcom SM, Hall PQ, Brown JW. 1976. The Double Bind: The Price of Being a Minority Woman in Science. Report of a Conference of Minority Women Scientists, Arlie House, Warrenton, Virginia. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1515 Massachusetts Avenue, N.

- Kath, L. M., Magley, V. J. 2014. Development of a Theoretically Grounded Model of Sexual Harassment Awareness Training Effectiveness Wellbeing: a complete reference guide. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118539415.wbwell031

- Clarke J. 1994. Pieces of the puzzle: The jigsaw method, p. 34-50. In Sharan, S (ed.), Handbook of Cooperative Learning Methods. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT.

- Gordon SE. 2014. Getting nowhere fast: The lack of gender equity in the physiology community. The Journal of General Physiology 144:1-3. doi:10.1085/jgp.201411240

- Filipovic J. 2019. The misogynist trolls attacking Katie Bouman are the tip of the trashpile. The Guardian. 17 April 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/17/katie-bouman-black-hole-image-online-trolls.

- Tworek H. 2014. Writing a Student Evaluation Can Be Like Trolling the Internet. The Atlantic. 21 May 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/05/writing-a-student-evaluation-can-be-kind-of-like-trolling-a-comments-section/371240/

- Blaster M. 2016. The sexual misconduct case that has rocked anthropology. Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaf4016

- Balter M. Leading Science Museum Turns the Page on a Prominent #MeToo Case. Scientific American. 21 May 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/leading-science-museum-turns-the-page-on-a-prominent-metoo-case/

- Pittman CT. 2010. Race and Gender Oppression in the Classroom: The Experiences of Women Faculty of Color with White Male Students. Teaching Sociology 38:183-196. doi:10.1177/0092055x10370120

- Williamson E, Ruiz RR, Steel E, Ashford G, Eder S. 2018. For Christine Blasey Ford, a Drastic Turn From a Quiet Life in Academia. The New York Times. 19 Sept 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/19/us/politics/christine-blasey-ford-brett-kavanaugh-allegations.html

- Mak T. 2018. Kavanaugh Accuser Christine Blasey Ford Continues Receiving Threats, Lawyers Say. NPR.org. 8 Nov 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/2018/11/08/665407589/kavanaugh-accuser-christine-blasey-ford-continues-receiving-threats-lawyers-say

- Dewsbury B, Brame CJ. 2019. Inclusive Teaching. CBE – Life Sciences Education 18:fe2. doi:10.1187/cbe.19-01-0021

- Gutiérrez y Muhs G, Niemann YF, González CG, Harris AP. 2012. Presumed Incompetent: The Intersections of Race and Class for Women in Academia. Utah State University Press.

- Clancy KBH, Nelson RG, Rutherford JN, Hinde K. 2014. Survey of Academic Field Experiences (SAFE): Trainees Report Harassment and Assault. PLoS ONE 9:e102172. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0102172

- Peterson DAM, Biederman LA, Andersen D, Ditonto TM, Roe K. 2019. Mitigating gender bias in student evaluations of teaching. PLOS ONE 14:e0216241. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216241

- Oluo I. 2018. So You Want to Talk About Race1st Edition. Seal Press, New York, NY.

- Hayes TL, Kaylor LE, Oltman KA. 2020. Coffee and controversy: How applied psychology can revitalize sexual harassment and racial discrimination training. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 1-20. doi:10.1017/iop.2019.84

- Roehling MV, Huang J. 2018. Sexual harassment training effectiveness: An interdisciplinary review and call for research. Journal of Organizational Behavior 39:134-150. doi:10.1002/job.2257

- Henderson C, Beach A, Finkelstein N. 2011. Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices: An analytic review of the literature. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 48:952-984. doi:10.1002/tea.20439

- Moyer RS, Nath A. 1998. Some Effects of Brief Training Interventions on Perceptions of Sexual Harassment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 28:333-356.

Article Files

Login to access supporting documents

Starting Conversations About Discrimination Against Women in STEM(PDF | 176 KB)

S1.Discrimination Against Women-Worksheet and Case Studies_1.docx(DOCX | 31 KB)

S2.Discrimination Against Women-Worksheet Appendix_1.docx(DOCX | 24 KB)

- License terms

Comments

Comments

There are no comments on this resource.