Priority Setting in Public Health: A lesson in ethics and hard choices

Published online:

Abstract

Undergraduate life sciences majors, many of whom aspire to work in healthcare and health research, can benefit from early exposure to ethical issues that they may encounter in these careers. This lesson plan introduces students to the tensions that health professionals face when choosing between obligations to individuals and public health interventions directed at communities. Do they save a life when it means they will not be able to protect others from harm? Do they protect a community at the cost of a life they could save? Although most people feel very strongly one way or another, few think about the moral traditions that form the basis of our choices. This lesson is designed to introduce two moral theories that are fundamental to the practice of medicine and public health - utilitarianism and deontology - and to give students the opportunity to explore how these theories can lead to very different ideas of right and wrong in health care practice. Small groups of students assume the role of medical teams in a case where a difficult choice must be made between two actions, each of which relies on one of the two moral theories. Students encounter different points of view and experience the tension of difficult decisions when there is no clear 'right' choice. The lesson includes a background PowerPoint deck, a discussion case, and formative and summative assessments. An optional list of suggested readings is also included. The lesson is designed as a 60-minute module.

Citation

Barchi, F. 2018. Priority Setting Public Health: A lesson in ethics and hard choices. CourseSource. https://doi.org/10.24918/cs.2018.5Lesson Learning Goals

At the end of this unit, students will:- Appreciate the key distinctions between public health and medicine

- Understand the ethical tensions that can arise in priority-setting when desired public health and individual health goals are in conflict

- Recognize that different moral theories/frameworks can result in different definitions of morally 'right' action

- Be sensitive to the constraints that may be placed on public health and patient care by one's moral obligations and duties to others and to his or her profession

Lesson Learning Objectives

At the end of this unit, students will be able to:- Define the central distinction between public health and medicine

- Apply objectives of public health and individual medical care in a particular situation to identify potential areas of conflict in priority setting

- Apply moral theories of utilitarianism and deontology to a particular situation to identify the course of action proponents of each theory would see as morally justified

- Identify the range of morally justifiable actions that might be available to a health professional in a particular setting

- Choose from among a range of possible actions in a particular health situation and articulate the ethical principles that would justify that choice.

Article Context

Course

Article Type

Course Level

Bloom's Cognitive Level

Vision and Change Core Competencies

Class Type

Class Size

Audience

Lesson Length

Pedagogical Approaches

Principles of How People Learn

Assessment Type

INTRODUCTION

The pursuit of science occurs within a social context that involves values, choices, and judgments about right and wrong (1). Undergraduate life sciences majors, many of whom aspire to work in healthcare and health research, can benefit from early exposure to ethical issues that they may encounter in such careers (2). Just as students need to learn scientific concepts and their application in the biological sciences, so too do they need opportunities to develop skills in ethical reasoning and decision-making in the face of moral challenges (3,4).

It is a truism that contemporary society is undergoing transformation at a dizzying pace not only in technology and in the dominant economic models, but in the culture that responds to both. What is less discussed, but no less clear, is that these developments present profound challenges for our ability to think critically about fundamental issues involving our changing human enterprises and the ethical choices they lead us to confront. Specifically, the changes in the scientific enterprise can appear to be so rapid that they outrun our ability to think critically about right and wrong, and more generally, what outcomes we should value as individuals and as members of a society. It is at precisely this juncture that higher education should train students to address challenges and opportunities inherent in science today through reflection, discussion, and debate.

This lesson plan has been developed to provide undergraduate biology faculty with a simple set of tools to introduce students to some of the ethical tensions that arise in public health. It relies on small-group discussion of a case in which students must, as a 'medical team,' choose a course of action when lives are at stake. The case is one of the 'standards' used in public health education to expose students to a fundamental difference between public health - which is concerned with the promotion of health in a population- and medicine -which treats the diseases and conditions of individual patients. A mini lecture using the provided PowerPoint deck introduces students to the two major moral theories that guide medicine and public health - utilitarianism and deontology. Utilitarianism, which emerged as a formal approach to moral evaluation and decision making in the 19(th) century, holds to the view that an action derives its moral worth from the amount of 'utility' that it produces. In other words, the morally right action is that action which produces the most good or benefit for the greatest number in a given situation (5). Utilitarianism is a form of consequentialism, in that actions are judged not on their intrinsic moral worth but rather on the consequences that they produce (6). Deontology, by contrast, judges the moral worth on one's actions not on the basis of consequences or benefit, but rather according to a set of rules to which one is bound by duty (5). An action is deemed to be the morally correct action if it upholds one's duty or obligation to a moral rule. Utilitarianism has long been accepted as the underlying moral 'compass' that drives public health decision making, i.e. in determining the best course of action to protect the health of the greatest number of people, while the practice of medicine is more commonly associated with deontological theory due to its emphasis on physicians' duties to their patients.

Case discussion has been identified as an effective way to expose students to ethical issues and to build ethical reasoning skills (7,8). In this lesson, utilitarian and deontological theories serve as the 'toolkit' that students, working in small groups, will use to guide their decision making regarding how a medical team should handle an emergency situation in which lives may hang in the balance.

INTENDED AUDIENCE

This lesson plan was designed for 3rd- and 4th-year undergraduates in the life sciences, and may be used as a stand-alone unit in any course in which concepts relating to human biology and disease are being introduced. In international settings in which students enter medical school immediately following secondary school as part of a six-year curriculum, the unit is suitable for students in pre-clinical training.

REQUIRED LEARNING TIME

This unit is designed as a 60-minute unit, inclusive of a mini-lecture (Supporting file S1), small-group and plenary discussion of a case (Supporting files S2 and S3), and a formative assessment (Supporting file S4). The summative assessment (Supporting file S5), which is administered as part of activities following the class in which the unit was used, may be administered as a stand-alone graded quiz or combined with other questions in a mid-term or final exam.

PRE-REQUISITE STUDENT KNOWLEDGE

There is no pre-requisite student knowledge for this lesson.

PRE-REQUISITE TEACHER KNOWLEDGE

There is no pre-requisite teacher knowledge for this lesson. The PowerPoint deck (Supporting file S1), the plenary discussion questions and summary answers (Supporting file S3), and the assessment answer keys and discussion guide (Supporting files S6) provide ample information even for those with limited familiarity with moral philosophy. Teachers in the life sciences who have not previously worked with the moral theories associated with medicine and public health may wish to consult one or more of the background readings included in Supporting file S7. The first listed resource, the chapter on moral theories by Beauchamp & Childress in their book, Principles of Biomedical Ethics provides a brief but detailed overview of utilitarianism and deontology (5).

SCIENTIFIC TEACHING THEMES

This lesson provides undergraduate biology teachers with a fun and highly interactive way to introduce the theme ethical decision-making into discussions about science involving human patients, subjects, and populations.

ACTIVE LEARNING

Students work in small groups to explore lesson content. Each group assumes the role of a medical team that must choose between completing its assignment to vaccinate as many young children as possible against a potentially fatal disease and saving the life of an accident victim. Each group must reach a consensus through discussion on the 'right' course of action and must identify and share the reasons for its choice with other groups.

ASSESSMENT

- Formative assessment: This lesson plan includes an ungraded quiz/exercise that is used in class to help students see if they are grasping the important concepts in this unit. The quiz presents a vignette illustrating another case of priority setting; students are asked to answer three multiple choice questions and one short answer question. The quiz is first completed individually by each student. The quiz is then 'retaken' as a group exercise in which students in each group must discuss and agree among themselves on the correct answers. (See S4. Priority setting in public health: Formative assessment, and S6 Priority setting in public health: Assessment answer keys and discussion guide.)

- Summative assessment: The lesson also includes a summative assessment for use as a stand-alone graded test/homework assignment or as a component in a larger mid-term or final exam. The summative assessment includes three multiple choice questions and four open-ended short answer questions. (See S5. Priority setting in public health: Summative assessment and grading rubric, and S6 Priority setting in public health: Assessment answer keys and discussion guide.)

INCLUSIVE TEACHING

The case used in this lesson invites different opinions about the 'right' course of action for a medical team. Either choice may be justifiable depending on the moral theory that serves as a guide. Given the absence of a 'correct' answer, students are encouraged to explore different points of view without fear of being 'wrong'. Students often feel strongly about what the medical team should do, but the format of the lesson creates a safe space for them to hear other viewpoints and express their own.

LESSON PLAN

I developed this lesson plan to provide undergraduate biology teachers with a simple and fun learning exercise that introduces students to ethical challenges in priority-setting in public health. It does not require training in philosophy or bioethics for the teacher to use, and preparation is simplified by the tools that are provided with the plan.

Preparation for Class

I generally teach this module in a classroom setting in which students can work in small groups either at round tables or lab benches. In such a setting, teachers simply need to provide copies of the Discussion Case and the quiz as well as some means by which groups can record and provide a rationale for their choice of action. I generally use large sheets of newsprint and colored markers with tape for sticking finished reports to the walls, but this lesson also works well in classroom settings in which students have access to whiteboards and colored markers, or individual video monitors to which each group can connect using their laptops.

Using the Unit in Class

This lesson plan contains all of the components that teachers will need to teach the unit. These include:

- A PowerPoint deck on the different approaches of public health and medicine, as well as the moral theories that guide decision-making (Supporting materials S1)

- The discussion case: The Car Accident (Supporting materials S2)

- A list of suggested questions for a discussion of the case in plenary, with recommended answers (Supporting materials S3)

- A Formative Assessment/Ungraded quiz (Supporting materials S4)

- A set of questions and grading rubric that can be used to assess student learning as part of a summative assessment (Supporting materials S5). The summative assessment includes multiple-choice questions about 1) the difference between the approaches of public health and medicine and 2) a vignette based on a modern version of the Trolley Problem(9), as well as two open-ended questions relating to a case study calling for priority setting of a scarce health resource.(10)

- An answer key and discussion guide for both the formative and summative assessments. (Supporting materials S6)

- A list of additional resources if teachers want to read more about the two moral theories used in this unit (Supporting materials S7)

Use the PowerPoint deck (Supporting materials S1) at the start of the unit to provide students with a basic toolkit of moral theories that would typically be used by health professionals to make decisions. Following this, distribute the case (Supporting materials S2) and ask the students to work in small groups to determine what choice they will make. As a general rule, groups of 4-6 students work best for case discussions; this arrangement gives opportunity for all who wish to speak, and avoids a dampening effect on the conversation by those who are less inclined to speak. It is easiest if one is working in a seminar environment in which students can easily rotate or move their chairs to create groups, but it can work equally as well in large lecture halls simply by asking to students to self-identify groups by including those persons sitting in close proximity. This is a highly interactive phase of the unit, as students often feel quite strongly about the 'right' course of action and must work with their peers to arrive at a group consensus even when, at the outset, they disagree. Once the groups have recorded their choices and provided their rationales on paper, white board, or monitor, ask for a show of hands of those who chose each action. Ask one group from each 'choice' to provide their rationale, and give other groups making the same choice a chance to add any further thoughts on why their choice was the right one to make.

A list of questions with suggested answers (Supporting materials S3) is provided as part of this lesson plan so that you can lead a whole-class discussion of the case. This is particularly useful as it reinforces the material you have provided about the moral theories as well as prompts students to think more deeply about the ramifications of their choice.

At the conclusion of the unit, ask each student to complete the short ungraded quiz (Supporting materials S4) provided with the lesson. Each student should take the quiz independently. Although groups are sometimes quite close together, this should not be a concern for the formative assessment, which is a learning aid rather than a graded assessment of a student's ability to apply lessons learned. Students who have moved their chairs to form groups can simply move them apart somewhat and students who are working in a theatre setting can return to their usual forward-facing positions. Once the assessment has been completed, ask each group to reform and discuss the vignette described in the quiz and reach agreement on the correct answers. This discussion provides an opportunity for students to learn from each other. Misconceptions can be discussed in plenary, but it is likely that students working collectively will arrive at the correct answers.

Materials to use for a summative assessment of student learning (Supporting materials S5) are provided in the form of a set of questions that may be used as a stand-alone on-line assignment/test following the class in which the module is taught or incorporated into a larger mid-term or final exam. An answer key as well as a discussion guide that explains answers and offers insights on the content you should expect to see in students' responses to open-ended questions is provided (Supporting materials S6).

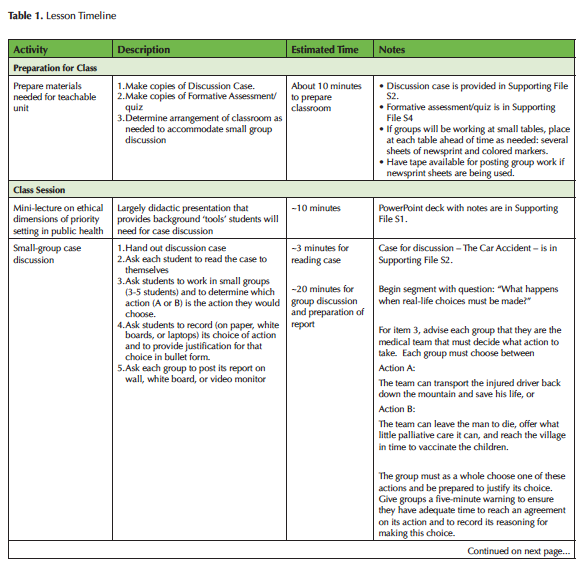

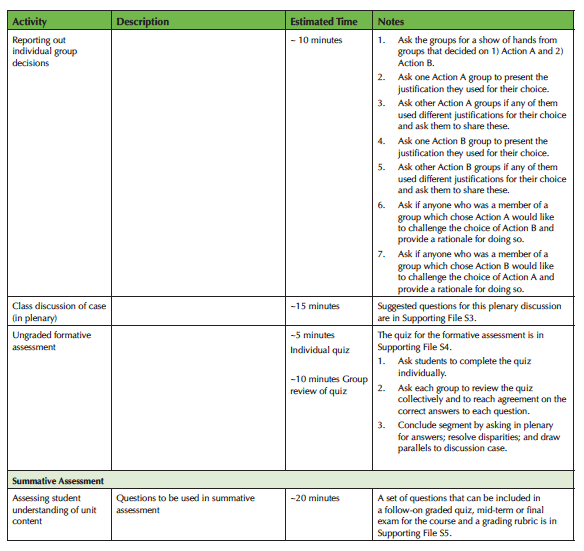

The following Lesson Timeline in Table 1 provides additional detail on the use of this unit.

Table 1. Teaching Timeline

Table 1 continued

TEACHING DISCUSSION

This lesson uses small-group, case-based discussion as the primary learning tools for students. In fall 2017, colleagues and I used this unit in a class with undergraduate STEM students at Rutgers University and subsequently in a seminar with counterparts at the Universidad Francisco Marroquin School of Medicine in Guatemala City, Guatemala. In both settings, the unit was enthusiastically received by the students and the case prompted energetic discussion.

Most students base their choices on an emotional reaction to the case; the challenge is getting them to think about what their choices might be if they used the moral theories to which they have been introduced in the mini-lecture. Moral theory for many people can seem impenetrable and irrelevant in the modern day; by giving students the opportunity to apply a theory rather than simply memorize its principles, we give them a chance to see theories at work in situations that may be at odds with their own beliefs. The plenary discussion of the case is an important opportunity for reinforcing the basic tenets of the theories and for encouraging students to reflect on how two very different sets of moral 'rules' can lead to very different actions. Students often have difficulty objectively thinking through how to apply a theory in a real life situation, particularly if they like the underlying principle of the theory but not the action it requires. For example, some students are strong advocates of a utilitarian perspective on health (doing the greatest good for the greatest number) but express a reluctance to abandon an injured person whose life it is in their power to save. The competing 'duties' of these two theories can expose sharp differences in people's choices and the reasons behind them. Importantly, the exercise makes students look at more than one side of an argument; in classes in which I have used this unit, students often took a position immediately and adamantly, only to shift in their perspective as they listened to their peers offer competing points of view. I've had students truly surprised by how their peers look at the discussion case. The undergraduate medical students in Guatemala, for example, were unanimous in their conviction that the medical team should abandon the injured driver in order to reach the children in time for the vaccination campaign (See Discussion case, The Car Accident, Supporting file S2). The students in the United States were shocked that students who aspire to be physicians would so readily abandon a life. The ensuing discussion, however, gave the US students the opportunity to look at the situation through someone else's eyes. For the students in Guatemala, the choice was between the privileged few (the driver who could access a hospital and the team with careers in the city) and the people of the 'highlands' who have been treated unfairly and lacked and/or been denied access to basic health care for most of their country's history. For the Guatemalan students, deciding what was the 'right' action was not an issue of weighing one's moral duties but one of upholding the human rights of a marginalized group.

In the future, I would allow more time to discuss the vignette used in the quiz (reference the relevant supporting material here). Interestingly, while students were able to identify how different moral theories would lead to different choices, their reactions to the actions of the helicopter pilot in the formative assessment vignette - to leave the medic on the ground rather than risk infection of those at base camp - were often at odds with the choices many made to save one life while leaving many children at risk. Discussion as to why their choices may look different could open up yet more opportunities for students to reflect on their reasoning and to be exposed to dissenting views. In order to make time for such a discussion in future classes, it might be adequate to use the explanatory videos on utilitarianism (http://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary/utilitarianism) and deontology (http://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary/deontology) that have been developed by the McCombs School of Business, University of Texas-Austin. These YouTube videos, links to which are also provided in Supporting Materials S7, are short and would require less time.

SUPPORTING MATERIALS

- S1 Priority setting in public health: PowerPoint Deck for Mini Lecture

- This PowerPoint deck introduces in very simplified form the different approaches taken by public health programs and the practice of medicine, and two moral theories - utilitarianism and deontology - that can be used to prioritize health resources.

- S2 Priority setting in public health: Discussion case

- This lesson is centered on small-group student discussion of this case - The Car Accident - in which a medical team must choose between two courses of action by referencing a set of moral theories that are commonly used for decision-making in health care and introduced in the mini-lecture for this lesson.

- S3 Priority setting in public health: Plenary discussion questions and summary answers

- This set of questions can be used to elicit classroom discussion from students following the small-group activity.

- S4 Priority setting in public health: Formative assessment/Ungraded quiz

- This ungraded quiz can be used in class at the end of the lesson to help teachers and students address learning gaps that need to be addressed if learning objectives are to be met.

- S5 Priority setting in public health: Summative assessment and grading rubric

- This summative assessment can be used as a free-standing on-line graded activity or incorporated into course mid-terms or final exams. It can also be used in a class following the one in which this lesson was covered to reinforce lesson concepts.

- S6 Priority setting in public health: Assessment answer keys and discussion guide

- This file provides the answers to the multiple-choice questions and suggests content that an instructor should expect to find in students' answers to the open-ended questions.

- S7 Priority setting in public health: Resources

- This file lists some suggested readings that may provide teachers and students with additional information about the moral theories used in this lesson.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Acknowledgment is due Drs. María Lorena Aguilera and Sergio N. Martinez Siekavizza from the Universidad de Francisco Marroquin School of Medicine (UFM) for their collaboration in pilot testing and evaluating this lesson. Special thanks are due to the many students at UFM and Rutgers University- New Brunswick who have participated in this lesson and provided feedback.

The development of this teachable unit draws on work from the Summer Institutes/Howard Hughes Medical Institute on assessment and backward design.

References

- Lindell TJ, Milczarek GJ. 1997. Ethical, legal, and social issues in the undergraduate biology curriculum. Journal of College Science Teaching. 26(5):345.

- Johansen CK, Harris DE. 2000. Teaching the ethics of biology. The American Biology Teacher. 62(5):352-8.

- Clarkeburn H, Downie JR, Matthew B. 2002. Impact of an ethics programme in a life sciences curriculum. Teaching in Higher Education. 7(1):65-79. DOI: 10.1080/13562510120100391

- Downie R, Clarkeburn H. 2005. Approaches to the teaching of bioethics and professional ethics in undergraduate courses, Bioscience Education, 5:1, 1-9, DOI: 10.3108/beej.2005.05000003

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. 2012 Moral theories. In Beauchamp, TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics (7(th) Ed.) New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 351-389. ISBN-10:0199924589

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2015. Consequentialism,. Accessed June 7, 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consequentialism/

- Herreid CF. 2005. Using Case Studies to Teach Science. Education: Classroom Methodology. American Institute of Biological Sciences. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED485982.pdf Accessed April 15, 2018

- Thistlethwaite JE, Davies D, Ekeocha S, Kidd JM, MacDougall C, Matthews P, Purkis J, Clay D. 2012.The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 23. Medical Teacher. 34(6):e421-44.DOI: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.680939

- Foot P. 1967. The problem of abortion and the doctrine of the double effect. Oxford Review. 5: 5-15.

- Smith MJ, Viens AM. 2016. Case 6: Critical care triage in pandemics. In DH Bennett, LW Ortmann, A Dawson, C Saenze, A Reis, G Bolan. Eds. Public health ethics: Cases spanning the globe. London: SpringerOpen, pp. 90-94.

Article Files

Login to access supporting documents

Priority Setting in Public Health: A lesson in ethics and hard choices(PDF | 126 KB)

S1 Priority setting in public health_PowerPoint deck for mini lecture.pptx(PPTX | 508 KB)

S2 Priority setting in public health_discussion case.docx(DOCX | 19 KB)

S3 Priority setting in public health_Plenary discussion questions and summary answers.docx(DOCX | 19 KB)

S4 Priority setting in public health_Formative assessment_ungraded quiz.docx(DOCX | 16 KB)

S5 Priority setting in public health_Summative assessment.docx(DOCX | 37 KB)

S6 Priority setting in public health_assessment answer keys.docx(DOCX | 23 KB)

S7 Priority setting public health_ Resources.docx(DOCX | 12 KB)

- License terms

Comments

Comments

There are no comments on this resource.