Expanding the Reach of Crop Plants for Food Security: A Lesson Integrating Non-Majors Students Into the Discussion of Food Diversity and Human Nutrition

Editor: Valerie Haywood

Published online:

Abstract

University general education (GE) courses host students with various academic backgrounds, interests, and perspectives. Engaging students in GE classes with agricultural issues can be challenging because of the diverse interests of students and the multifaceted nature of agricultural issues. Additionally, large-enrollment GE courses offered in auditorium style classrooms present physical constraints to collaborative and experiential learning. Here, we present an easy to implement lesson module in a GE course that solicits and integrates students' perspectives into in-class discussions and also leverages a discussion topic-centered writing component. This compact set of discussions is centered on the utilization of nutritious, but currently underutilized, grain crops from around the world that have historically functioned as a staple food in their respective cultures. The nutritional advantages of these grain crops as well as the agricultural, economic, and social constraints surrounding their global utilization are understandable to students in GE courses. In fact, the academic and geographic diversity of students in GE courses can use their personal experience with these crops and bring these considerations to light during in-class discussion. This lesson module serves both to familiarize students with food security related issues and to improve student agricultural literacy in a GE classroom setting. We envision that this lesson is suitable for courses within and beyond the plant science discipline. In addition, this lesson is amenable to implementation in classes that are either constrained in their physical ability to promote active learning, their contextual ability to discuss plant-related subject matter, or both.

Primary image: An arranged collection of seeds from each underutilized cereal and pseudocereal used in this lesson module. The authors took the photo and prepared this figure.

Citation

Bekkering CS, Tian L. 2020. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security: A lesson integrating non-majors students into the discussion of food diversity and human nutrition. CourseSource. https://doi.org/10.24918/cs.2020.39

Society Learning Goals

Plant Biology

- Plants and Society

- What is biodiversity, how do humans affect it, and how does it affect humans?

Science Process Skills

- Process of Science

- Locate, interpret, and evaluate scientific information and primary literature

Lesson Learning Goals

Students will:

- know the nutrient profile of major staple grain crops that indicate their nutritional benefits and limitations.

- compare and contrast underutilized grain crops and major staple grains in terms of nutritional quality, traditional uses, and modern applications.

- recognize and explain the role that crop diversity plays in the global food system.

Lesson Learning Objectives

Students will be able to:

- evaluate the nutritional and agronomic advantages and limitations of different underutilized grain crops in the context of agricultural systems around the globe.

- distinguish the economic and social considerations that factor into the incorporation of currently underutilized grain crops in the global food system.

- relate issues surrounding crop cultivation and utilization to global challenges such as poverty, inequity, and food security.

- synthesize points from peer discussion and findings from scientific literature into written reports.

Article Context

Course

Article Type

Course Level

Bloom's Cognitive Level

Vision and Change Core Competencies

Vision and Change Core Concepts

Class Type

Class Size

Audience

Lesson Length

Pedagogical Approaches

Principles of How People Learn

Assessment Type

SCIENTIFIC TEACHING THEMES

Active Learning

In addition to group discussion, our lesson takes advantage of the teaching strategies below to encourage student engagement (21).

- Ask open ended questions

- Think-pair-share

- Hand raising (with inclusion of additional voices where possible)

- Integrate culturally diverse examples

- Monitor student participation

Assessment

Assessment of student learning took on two forms. Low-stakes formative assessments were conducted through observation of students' responses to open-ended questions and monitoring of think-pair-share activities. In addition, an outline of the writing assignment (a summative assessment in this module as discussed below) was due soon after the discussion periods and two weeks before the due date of the completed essay (see "Lesson Plan" in the next section). Evaluation and grading of the essay outline (ten percent of the writing assignment points) provided effective feedback on students' learning of the module and guided their preparation of the essay. The outlines and the final essays were graded based on students' articulation of topics from in-class discussion, integration of literature into their arguments, and on general writing composition. Students were made aware of this grading scheme before the discussion to encourage involvement in the discussion.

Summative assessments encompassed a writing assignment in the context of the discussion (Supporting Files S1. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Writing Assignment 1) and questions on the midterm exam. The writing assignment served as a summative assessment for the lesson by giving us a means to gauge student understanding of the material. The writing assignment also functioned as a formative assessment within our course as a whole by enabling us to foster improvements in writing quality through feedback and tuning of later course material ahead of a separate, but similarly assessed writing assignment later in the term. Indeed, improvements to student writing quality were seen on the second writing assignment, which indicates a sustained impact of the lesson module on student writing efficacy.

In addition to the writing assignment, questions based on the content of the discussions were incorporated into the midterm exam of our course (Supporting Files S2. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Midterm Questions Related to Discussion) and functioned as a summative assessment of the lesson module. The midterm was a standard multiple-choice exam, with questions from the in-class discussion amounting to ten percent of the content and weight of the exam. Students were notified of this midterm component and of the writing assignment before the lesson module to further encourage in-class participation (see Lesson Plan).

Inclusive Teaching

Our lesson used crops that have historical connections to several different regions around the globe and that can be found on shelves of some grocery stores. As such, the discussion was amenable to the personal experiences of individuals from a multitude of backgrounds. In our discussion, student inputs from Central American, South American, and Asian cultural contexts were included to great effect. Alongside of that, inputs from other students that had consumed products made from teff, chia, and quinoa were woven into the discussion as well. While surveying discussions taking place around the classroom, we noticed parallel themes from other crops (e.g., kale, avocado, and maize) emerging in conversation as well.

In terms of instructor practices, involvement of a broader group of individuals was encouraged. During breakout group discussions, the instructor and the teaching assistant served both to stimulate discussion of quieter groups and to motivate involvement of more students in the breakout discussions. Also, though the whole-class discussion was guided mostly by about a dozen group reporters, both the instructor and the teaching assistant called upon students that were found to have novel inputs from the breakout discussion to give them an opportunity to showcase their ideas.

LESSON PLAN

The Writing Assignment

One week before the lesson module, the writing assignment was posted to the course website and announced in class. This writing assignment prompted students to recommend an underutilized grain crop of their choice to the purchasing team of a local food Co-Op (Supporting Files S1. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Writing Assignment 1). Students were asked to consider the nutritional advantages of their chosen grain crop relative to the major staple grains, the social and agricultural issues surrounding the possible utilization of their grain crop, and marketing strategies to promote the crop. Preparation for this writing assignment was noted to students as a key objective of the in-class discussion periods.

An outline for the writing assignment was due three days after the in-class discussion (i.e., the conclusion of the lesson module) (Table 2; Supporting Files S1. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Writing Assignment 1). Agricultural and social concerns of their chosen underutilized grain crop were necessary components of the outline and the final essay submission, motivating students to engage in the discussion with their classmates. The complete essay was due two weeks after the submission of the outline (Supporting Files S1. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Writing Assignment 1). Students were expected to incorporate refereed scientific literature into their essay by integrating at least five peer-reviewed sources into their work. An extra credit, out-of-class library session was given twice before the in-class discussion in which a university librarian demonstrated the use of electronic resources for searching scientific literature for the writing assignment (Table 2).

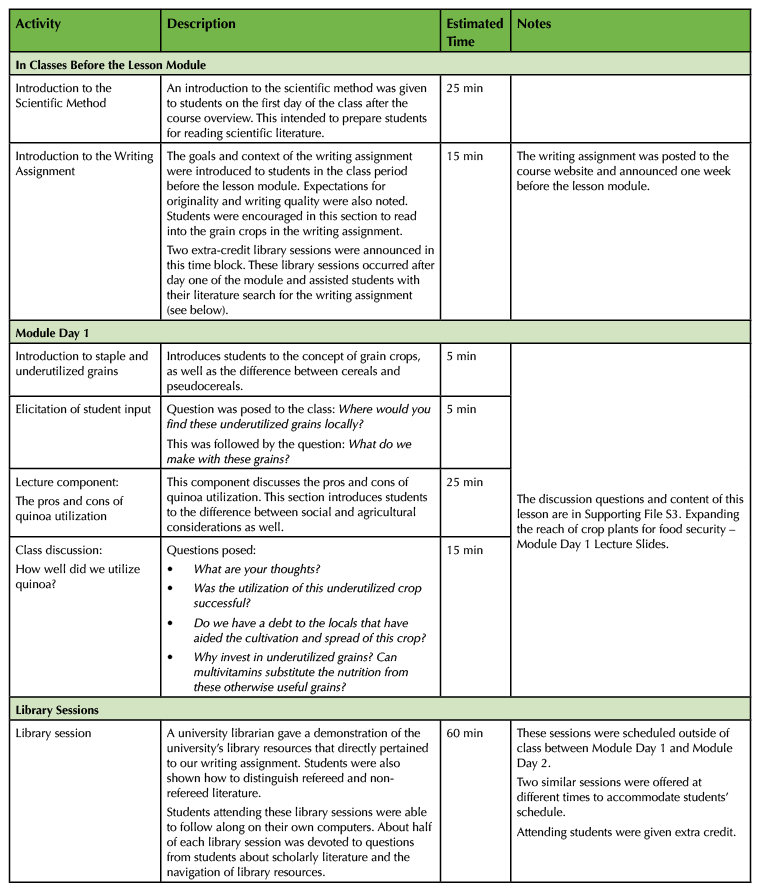

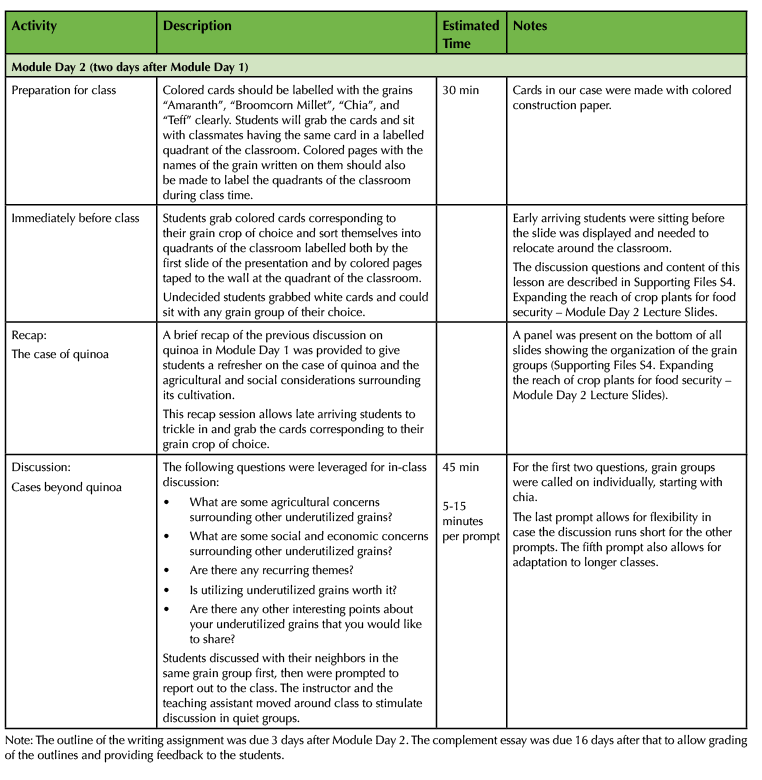

Table 2. Lesson timetable for the discussion module and for course components leading up to and contributing to the lesson module.

Table 2. Lesson timetable for the discussion module and for course components leading up to and contributing to the lesson module (continued).

The Discussion Module

Before the Discussion

Prior to the lesson module, students were introduced to major staple cereals that are rich in carbohydrates but generally low in vitamins and minerals, and to the lack of diversity present in the global food system. The lesson module (including the discussion periods), the posting of the writing assignment, and the library sessions noted above were all announced in the preceding two classes as well (Table 2).

Module Day 1

Day one of the module began with an introductory mini-lecture on the major staple grains wheat, rice, and maize, which led into a segment about underutilized grains (Supporting Files S3. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Module Day 1 Lecture Slides). In our class, this segment functioned as a re-introduction to the different types of grain crops, as cereals and pseudocereals were defined in a previous class period. The introduction to underutilized grains used images of several cereal or pseudocereal grains (Supporting Files S3. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Module Day 1 Lecture Slides) and surveyed students for their familiarity with each of the grains shown. After the mini-lecture, students were encouraged to share with the class any dishes that they knew of that incorporated the underutilized grains displayed. Students reported out several dishes during this portion of the class—dishes that often highlighted the diverse experiences of the class members.

After several minutes of students reporting out, a second lecture phase of the class focused on a case study of quinoa, a nutritious, underutilized pseudocereal grain. Quinoa's journey to broader utilization has been tumultuous, with both social and agricultural considerations factoring into its wide adoption (22,23) (Supporting Files S3. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Module Day 1 Lecture Slides). The economic and social concerns surrounding quinoa utilization have been the subject of many journalistic and academic investigations, making it a great place to start the discussion of leveraging traditional crops for human health and food security. The lecture portion on quinoa took up the middle of the class period and detailed the social and agricultural concerns surrounding quinoa, as well as the distinction between social and agricultural concerns more broadly. This lecture portion concluded with personal accounts from quinoa farmers and consumers that showed these concerns manifesting themselves in the South American communities that have consumed quinoa for generations (Table 2; Supporting Files S3. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Module Day 1 Lecture Slides).

The final portion of the class period was allocated to open class discussion on the case of quinoa. The prompts below were used to cultivate discussion (Supporting Files S3. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Module Day 1 Lecture Slides):

- What are your thoughts?

- Was the utilization of this underutilized crop successful?

- Do we have a debt to the locals that have aided the cultivation and spread of this crop?

- Why invest in underutilized grains? Can multivitamins substitute the nutrition from these otherwise useful grains?

The prompt "What are your thoughts?" was given to the class first, and responses were taken from individual students that raised hands, with no think-pair phase used for the first prompt. Each successive prompt was done one by one as a brief think-pair-share activity (21,24). Our class had many students participating in the discussion with responses both agreeing and disagreeing with the presented question. The last question stirred the most discussion between students, with individuals reporting out eagerly and often without the need for instructor intervention. Day one ended by announcing again the coming discussion during the next class period and by noting the parallels between the in-class discussion and the theme of the writing assignment. Students were also reminded to select a grain to focus on for their writing assignment and the in-class discussion before the next class period. Lastly, the extra credit library sessions noted above were announced again at the end of this period. The library sessions covered similar materials and were scheduled at different times out-of-class to accommodate students' schedules.

Module Day 2

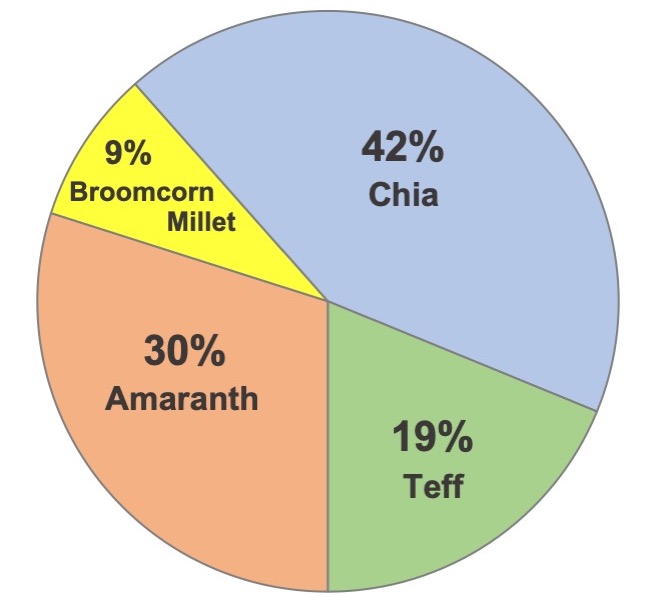

The second day of the module (two days after the preceding lecture) began with students picking up a colored card corresponding to their chosen underutilized grain and sitting in a quadrant of the classroom with other students that had selected on same grain (Supporting Files S4. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Module Day 2 Lecture Slides). A white "undecided" card was available to students that were unsure of their grain choice. However, no students picked this card in our class. Though there was a strong preference toward chia and less of a preference for broomcorn millet in our class (Figure 1), each group had enough students to enable discussion.

Figure 1. Grain choices by students for the in-class discussion.

As students were getting settled, the instructor gave a five-minute recap of the social and agricultural concerns surrounding quinoa cultivation (Table 2). The card colors were noted on the bottom of all slides so that late arrivals could get oriented (Supporting Files S4. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Module Day 2 Lecture Slides). Transparent bags with each of the five underutilized grains introduced on Day 1 of the module were passed around the class during the introduction as well. Note that quinoa was discussed on Day 1 and not the focus of discussions on Day 2. After the brief recap, the following discussion questions were used one by one:

- What are some agricultural concerns surrounding other underutilized grains?

- What are some social and economic concerns surrounding other underutilized grains?

- Are there any recurring themes?

- Is utilizing underutilized grains worth it?

For each question, students in each grain group discussed among themselves for two to five minutes, with the instructor working to engage less active groups of students. For the first prompt, members of each grain group were told to report out, starting with the group with the largest number of members (chia in our case). For successive prompts, a mixture of hand-raising and cold-calling was used to take advantage of self-nominated group reporters while also giving quieter students a chance to include their perspectives.

The third and fourth discussion prompts served multiple purposes. Firstly, conversations around these prompts brought together and re-packaged the points from prior discussions, allowing students to synthesize the ideas from prior discussion among themselves with only minimal instructor input. This portion of the discussion also served to address key components of the writing assignment, namely the section in which students suggest a marketing strategy for their respective grains at the local food Co-Op. In our classroom, the open discussion surrounding the fourth discussion prompt was robust and spontaneous. Perspectives from students came from many different angles and required only minimal synthesis and repackaging by the instructor.

In the case of extra time, a fifth discussion prompt was prepared for students: "Are there any other interesting points about your underutilized grains that you would like to share?" (Supporting Files S4. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Module Day 2 Lecture Slides). Discussion of the worth of utilizing underutilized grains used up the remaining class time, so this discussion question was not used in our class. We believe that this last prompt could be used in longer classes either to start the discussion or to make fruitful use of remaining time after the fourth discussion question.

Points raised by students during the discussion were summarized and posted to the course web page (Supporting Files S5. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Class Discussion Points). Students were informed that content from the discussion would be present on the first midterm exam and were encouraged to look back on those discussion notes. We acknowledge that focal points of discussion can vary widely based on the backgrounds of the students, but we believe that many of the points raised by our students are likely to appear in other classrooms as well.

TEACHING DISCUSSION

We were interested in getting student feedback on the lesson. Student input was elicited for the lesson using a five-point Likert scale and an open response question where students could supply input for the improvement of the lesson (Supporting Files S6. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Discussion Effectiveness Survey). This survey was anonymous and filled out by approximately three quarters of the students (87 students out of 117). The Likert scale prompts on this survey were the following:

- The discussion sections improved my understanding of underutilized grain crops, including their advantages and limitations.

- The discussion sections improved my ability to write critically about these underutilized crops in the first writing assignment.

- Inputs from students were incorporated well during the discussion sections.

- I was personally interested in the content of the discussion sections.

- The discussions were executed effectively.

Likert-Scale Responses

Responses to the Likert scale portion of the survey were overall positive. For the first three prompts and the fifth prompt, over 60% of students agreed or strongly agreed with the statement and only less than 12% disagreed, with disagreement being close to zero for some prompts. In addition, the positive impact of the discussion sessions was also reflected in the writing assignment. Both STEM and non-STEM major students were able to proficiently integrate a variety of social, agricultural, and economic factors related to their chosen grain crop into their essays. The average score on the writing assignment was 90.8% out of 100%.

In response to the prompt "I was personally interested in the content of the discussion sections," approximately 13% of the students disagreed with the statement and another 40% showed a neutral response. As a GE course, our class was comprised of students from a wide range of STEM and non-STEM majors, and a great majority of the students did not have an agricultural component to their degree program. Therefore, it is conceivable that some students may not have personal interest in the subject matter when entering this class, which is consistent with the observation of plant blindness in the general student body. On the other hand, the response to this question highlights the need for promoting agricultural literacy in GE courses, the inspiration that motivated us to design and deliver this lesson module in the first place. These efforts appear to have made a positive impact on students' learning. When anonymous teaching evaluations were conducted at the end of the quarter, students indicated that "the overall educational value of the course" was very good to excellent with the options of poor (1), fair (2), satisfactory (3), very good (4), and excellent (5).

Student Suggestions for Improvement

In the open-ended suggestions portion of the survey, students noted their perceptions toward the discussion session and often supplied suggestions for future discussions on the same subject. Aligning with the results of the Likert survey, most of the responses were very positive, with comments noting the diverse perspectives brought by classmates and the benefit of splitting the class into grain groups. The critical comments highlighted an aspect of the lesson that could be refined: students are not under a strict obligation to select or research their chosen grains before the in-class discussion. In our class, the writing assignment that requires students to select a grain crop was announced in advance. However, the writing assignment was designed to be due after the in-class discussion, allowing students to integrate information and resources from discussion into their assignment submissions. As shown in the responses to the Likert-scale survey, over 60% students agreed with the statement that "The discussion sections improved my ability to write critically about these underutilized crops in the first writing assignment". Nonetheless, students are not without previous experiences for the in-class discussion, and this likely accounts for the fact that the white undecided card was not picked by any students during the second day of the module. In fact, many personal experiences with these grain crops emerged in discussion—both from cultural heritage and from routine consumption in everyday dishes.

When moving this discussion module into another classroom, particularly in a semester system with a less compact course schedule, a slight modification to the class assignment such as the addition of a small, related assignment (e.g., a blog post or a reading assignment) before the discussion would give students more exposure to their chosen grain crop before the discussion. Having students work on a small assignment in advance may curb the lopsidedness toward chia as well. We noticed that when asked for a show of hands during in-class discussion for the question "How many of you had heard of your grain crop before?", raised hands were concentrated in the chia group. It is possible that relatively unprepared students may have defaulted to chia in the discussion because it was the grain crop those students had prior exposure to.

Adapting the Lesson for Other Classrooms

The lesson module presented here is easily adapted to other classrooms and institutions. In contrast to other larger-scale course reformations, this module has the advantage of being cost-effective and compact, enabling its incorporation into inflexible or underfunded courses. The compactness of this module and its writing assignment allows it to serve as a formative assessment for writing efficacy within courses that have improved writing ability as a learning goal, such as our GE course. This enables instructors to tailor subsequent course materials to meet specific learning and writing needs in their classroom. In addition, the global perspective of this easily installed lesson makes it a valuable addition to general courses with little or no plant biology component, which could help curb the decline of plant biology and agricultural science content in college classrooms (25).

Given that the decline in agricultural literacy among incoming undergraduate students has occurred in parallel to the decline of plant biology content in classrooms (6,11,26), fostering agricultural literacy in the classroom is another key benefit of the lesson module. It has been shown that prior agriculture coursework experiences were associated with greater understanding of agriculture related issues in incoming undergraduates (6). As such, we believe that this lesson module and its accompanying writing assignment can help foster agricultural literacy by having students in our course unpack agricultural related social, environmental, and economic issues in a case-study format. Furthermore, the integrated writing component of this lesson module enables it to be used in courses that fulfill institutional writing requirements aimed at resolving known writing gaps in incoming undergraduate students (27).

The lesson could be adapted in a number of ways to fit different classroom contexts. The length of time allocated to each discussion question could be extended or more discussion questions could be added (such as the unused fifth question noted on day 2) to accommodate longer class periods. The content of the lesson is also flexible. While we have opted to focus on these five grain crops, the lesson is not constrained to these specific grains. As students benefit from learning content that is relevant to them (16) and because the in-class discussion calls heavily on personal experiences, the underutilized crops at the center of this lesson can be changed to fit the social and agricultural context of the college or university. This allows the instructor to tailor the lesson to fit the personal experiences of the students while still anchoring the lesson in the interconnected concerns that surround plant cultivation by human society (4,11,29). Such personal experiences were noted in our classroom discussion for each of our grains, and these experiences added unique perspective to our Plants and Society course offering.

SUPPORTING FILES

- S1. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Writing Assignment 1

- S2. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Midterm Questions Related to Discussion

- S3. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Module Day 1 Lecture Slides

- S4. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Module Day 2 Lecture Slides

- S5. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Class Discussion Points

- S6. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security – Discussion Effectiveness Survey

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the students in our course for bringing their experiences in the discussion activities and for their willingness to supply feedback for the improvement of the lesson module. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Shu Yu for her assistance with the primary image of this article. We thank Kevin Abuhanna for assistance with images used during the lesson.

References

- FAO. 2018. Once neglected, these traditional crops are our new rising stars. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/fao-stories/article/en/c/1154584/. Accessed November 19, 2019.

- Wandersee JH, Schussler EE. 1999. Preventing plant blindness. Am. Biol. Teach. 61(2):82-86. https://doi.org/10.2307/4450624

- Jose SB, Wu C, Kamoun S. 2019. Overcoming plant blindness in science, education, and society. Plants, People, Planet, 1(3):169-172. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.51

- Amprazis A, Papadopoulou P. 2020. Plant blindness: a faddish research interest or a substantive impediment to achieve sustainable development goals? Environ Educ Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1768225

- National Research Council. 1988. Understanding agriculture: New directions for education. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/766

- Colbath SA, Morrish DG. 2010. What Do College Freshmen Know About Agriculture? An Evaluation of Agricultural Literacy. NACTA Journal 54(3):14-17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/nactajournal.54.3.14.pdf

- Krosnick SE, Baker JC, Moore KR. 2018. The Pet Plant Project: Treating Plant Blindness by Making Plants Personal. Am Biol Teach. 80(5):339-345. https://doi.org/10.1525/abt.2018.80.5.339

- Wandersee JH, Clary RM, Guzman SM. 2006. A Writing Template, for Probing Students' Botanical Sense of Place. Am Biol Teach. 68(7):419-422. https://doi.org/10.2307/4452030

- Chrispeels HE, Chapman JM, Gibson CL, Muday GK. 2019. Peer Teaching Increases Knowledge and Changes Perceptions about Genetically Modified Crops in Non-Science Major Undergraduates. Cell Biol. Educ. 18(2). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-08-0169

- Jabbour R, Pellissier ME. 2019. Instructor Priorities for Undergraduate Organic Agriculture Education. Nat Sci Educ. 48(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.4195/nse2019.06.0010

- Kovar KA, Ball AL. 2013. Two Decades of Agricultural Literacy Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. J Agric Educ. 54(1):167-178. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1122296

- Eck CJ, Edwards MC. 2019. Teacher shortage in school-based, agricultural education (SBAE): A historical review. J Agric Educ. 60(4):223-239. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.04223

- Smith A, Foster D, Lawver R. 2015. National Agricultural Education Supply & Demand Study 2014 Executive Summary. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.24700.23684

- Hovland K. 2014. Global learning: Defining, designing, demonstrating. American Association of Colleges and Universities.

- Bekkering CS, Tian L. 2019 Thinking outside of the cereal box: Breeding underutilized (pseudo)cereals for improved human nutrition. Front. Genet. 10:1289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.01289

- Chamany K, Allen D, Tanner KD. 2008. Making biology learning relevant to students: Integrating people, history, and context into college biology teaching. Cell Biol. Educ. 7(3):267-278. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.08-06-0029

- AAAS. 2009. Vision and change in undergraduate biology education: a call to action. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science. https://visionandchange.org/. Accessed March 2, 2020.

- Wood WB. 2003. Inquiry-based undergraduate teaching in the life sciences at large research universities: A perspective on the Boyer Commission Report. Cell Biol. Educ. 2:112-116. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.03-02-0004

- Bradford T, Hock G, Greenhaw L, Kingery WL. 2019. Comparing experiential learning techniques and direct instruction on student knowledge of agriculture in private school students. J Agric Educ. 60(3):80-96. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.03080

- Bransford JD, Brown AL, Cocking, RR. 2000. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9853

- Tanner KD. 2013. Structure matters: Twenty-one teaching strategies to promote student engagement and cultivate classroom equity. Cell Biol. Educ. 12(3):322-331. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-06-0115

- Depillis L. 2013. Quinoa should be taking over the world. This is why it isn't. - The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/. Accessed December 10, 2019.

- Livingstone G. 2018. How quinoa is changing farmers' lives in Peru - BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-45008830. Accessed December 10, 2019.

- Angelo TA, Cross KP. 1993. Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Balas B, Momsen JL. 2014. Attention "blinks" differently for plants and animals. Cell Biol. Educ. 13(3):437-443. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-05-0080

- Dale C, Robinson JS, Edwards MC. 2017. An Assessment of the Agricultural Literacy of Incoming Freshmen at a Land-Grant University. NACTA Journal 61(1):7-13. https://www.nactateachers.org/attachments/article/2523/NACTAJournalMarchIssue_2017.pdf#page=10

- Kellogg RT, Whiteford AP. 2009. Training Advanced Writing Skills: The Case for Deliberate Practice. Educ. Psychol. 44(4):250-266. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903213600

- Freeman S, Eddy SL, McDonough M, Smith MK, Okoroafor N, Jordt H, Wenderoth MP. 2014. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111(23): 8410-8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

- Lamm AJ, Harsh J, Meyers C, Telg RW. 2018. Can they relate? Teaching undergraduate students about agricultural and natural resource issues. J. Agric. Educ. 59(4): 211-223. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2018.04211

Article Files

Login to access supporting documents

Expanding the Reach of Crop Plants for Food Security(PDF | 253 KB)

S1. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security - Writing Assignment 1.docx(DOCX | 28 KB)

S2. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security - Midterm Questions.docx(DOCX | 15 KB)

S3. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security - Module Day 1 Lecture Slides.pptx(PPTX | 2 MB)

S4. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security - Module Day 2 Lecture Slides.pptx(PPTX | 158 KB)

S5. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security - Class Discussion Points.docx(DOCX | 17 KB)

S6. Expanding the reach of crop plants for food security - Discussion Effectiveness Survey.docx(DOCX | 17 KB)

- License terms

Comments

Comments

There are no comments on this resource.