To facilitate understanding of the fundamental genetic concept of the genotype-phenotype relationship in our introductory biology students, we designed an engaging multi-week series of related lessons about canine genetics in which students explore and answer the question, "How does the information encoded in DNA lead to physical traits in an organism?" Dogs are an excellent model organism for students since the genetic basis for complex morphological traits of various breeds is an active area of scientific research and dog DNA is easily accessible. Additionally, examination of students' pets offers a relatable, real-world, connection for students. Of the more than 19,000 genes that control canine genetics, simple genetic mutations in three genes are largely responsible for the coat variations of dogs –specifically, the genes that control hair length, curl, and the presence/absence of furnishings. In our lessons, students collect DNA samples from dogs, isolate and amplify targeted sections of DNA through polymerase chain reactions (PCR), and then sequence and analyze DNA for insertions and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutations. Utilizing gel electrophoresis and bioinformatics tools, students connect how the physical manifestation of traits is rooted in genetic sequences. Students also participate in discussions of scientific literature, group collaboration to construct a final poster, and presentation of their findings during a mock scientific poster conference. Through this module students engage in progressive exploration of genetic and molecular techniques that reveal how simple variations in a few DNA sequences in combination lead to a broad diversity of coat quality in domestic dog breeds.

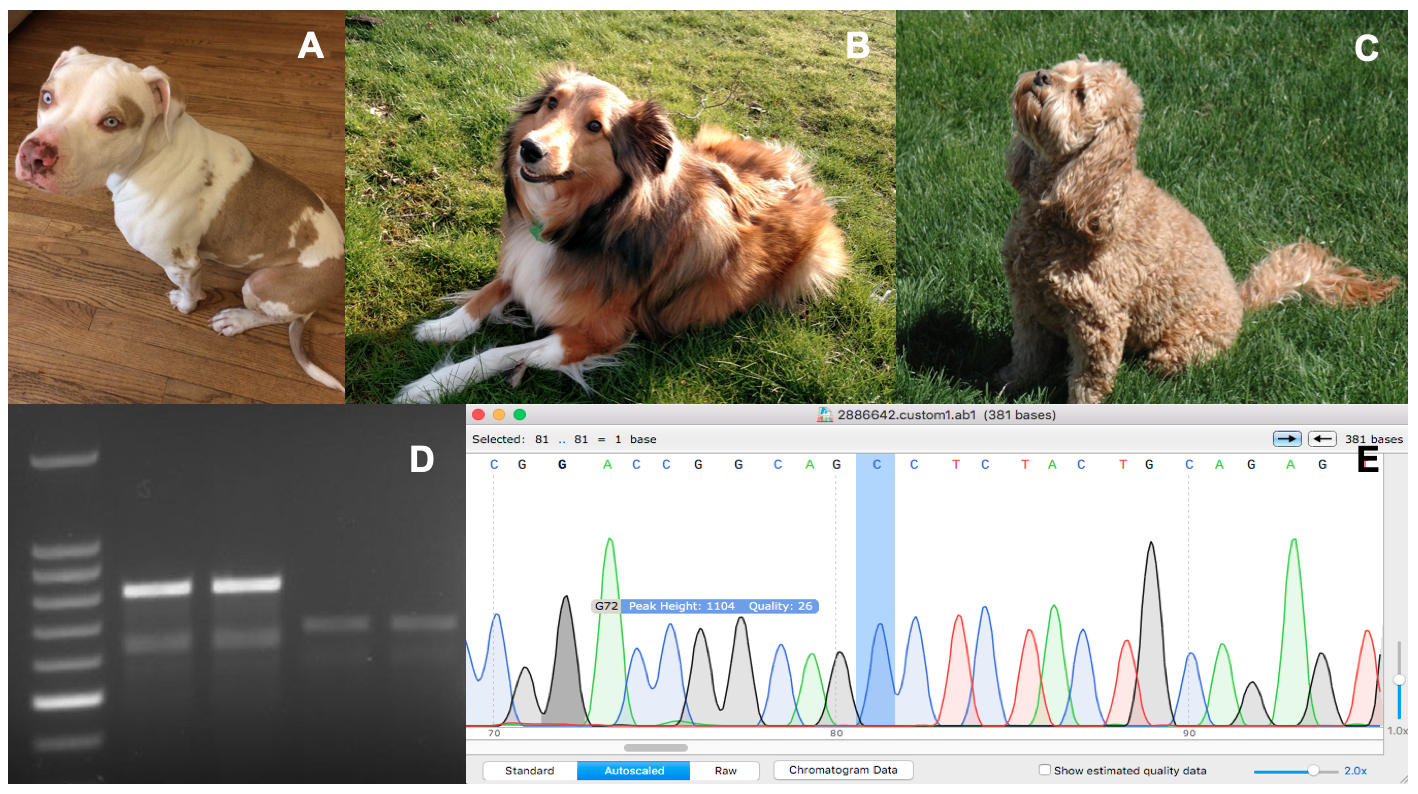

Primary image. Genetic Analysis of Canine Coat Morphologies. Three dogs with differing coat morphologies analyzed by students (A, B, C), an agarose gel post-electrophoresis (D), and a chromatogram of a DNA sequence highlighting a relevant mutation (E). This collage contains original images taken by authors and course participants.

Emily Rude onto Genetics

@

on